Indigenous elders and ritual specialists help to unlock the meaning of ancient Amazonian rock art

Victor Caycedo

Archaeologists documenting tens of thousands of rock art motifs in the Colombian Amazon have been consulting with Indigenous elders and ritual specialists to help interpret their meaning.

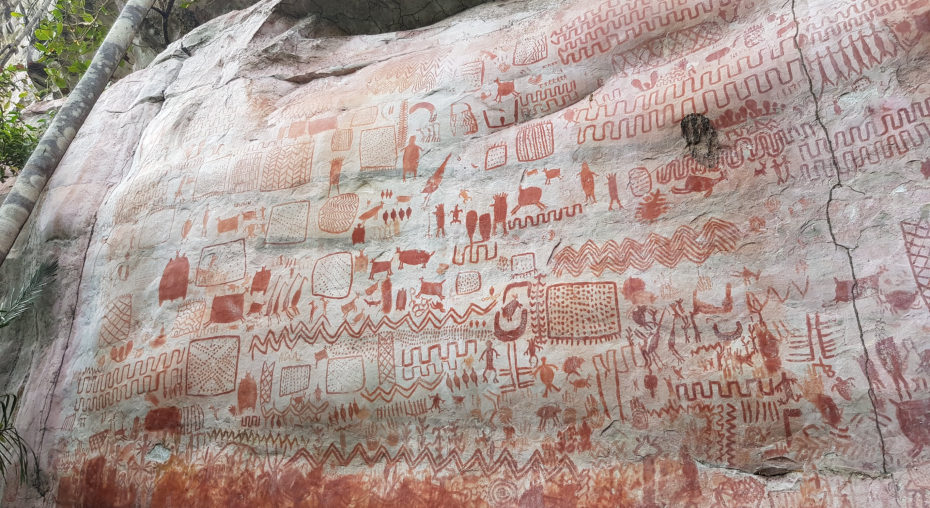

Ochre paintings depicting native wildlife that also feature heavily in creation stories – such as jaguars and anaconda – and scenes of people transforming into animals have been discovered at numerous sites in the country, with some estimated to date back more than 11,000 years.

Now, researchers at the University of Exeter and partner institutions in South America working in the Serranía De La Lindosa region of north-west Colombia have brought in more local experts to view the panels and record their interpretations.

Combining these Indigenous accounts with other sources of research has led them to conclude that the art speaks of ritual specialists negotiating spiritual realms, the transformation of bodies, and the intertwining of human and non-human worlds – rather than a more literal record of the environment they lived in and the species they encountered.

The findings are summarised in A World of Knowledge’: Rock Art, Ritual, and Indigenous Belief at Serranía De La Lindosa in the Colombian Amazon, which is published in the special issue of Advances in Rock Art Studios.

“Indigenous descendants of the original artists have recently explained to us that the rock art motifs here do not simply ‘reflect’ what the artists saw in the ‘real’ world,” says Professor Jamie Hampson, lead author and archaeologist in the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, for the University of Exeter, Cornwall. “They also encode and manifest critical information about how animistic and perspectivistic Indigenous communities constructed, engaged with, and perpetuated their ritualised, socio-cultural worlds. As Ulderico, a Matapí ritual specialist, told us in front of one of the painted panels in September 2022, ‘you have to look at [the motifs] from the shamanic viewpoint’.”

Archaeologists at the University of Exeter have been working in the region for the past six years, primarily through the European Research Council-funded LASTJOURNEY project, which has investigated the demographic shift of peoples into South America.

Over three field seasons between 2021-23, the research team accompanied 10 Indigenous elders and ritual specialists to six of the panels documented at the Cerro Azul outcrop of the Serranía De La Lindosa. Speaking in Spanish, or Indigenous languages including Desana, Tukano, and Nukak, the elders were recorded and their testimonies translated.

Scenes of therianthropic transformation were of great interest to the elders, and they repeatedly highlighted images including avian/human, sloth/human, lizard/human and snake/bird/human figures.

Tukano-speaker Ismael Sierra, pointing to paintings at a site called La Fuga in 2023, said: “So here are the animals that are there, they exist in that mountain range that was formerly and still is, but it is in the spiritual world… These are men with two arms, they are giants that exist in that spiritual maloca (house)… there is an animal, a panther lion that has two heads, one head here and the other here, instead of a tail it has a head, they are from the spiritual world.”

Victor Caycedo, a Desana elder, who accompanied the team to the sites in 2022 and 2023, told the researchers that the paintings were themselves created by spirits. Pointing to motifs high up the rock face, he asked rhetorically: “How would you paint up there? How would you do it? They didn’t do it with a ladder…they didn’t do it with some big devices that were put there… Why? Because the natives in the old days lived spiritually… They were a spirit…”

Animals inhabiting and symbolizing liminal spaces – those who move between earth, water, and sky, such as anacondas, jaguars, bats and herons – and activities such as fishing were also picked out by the elders as imbued with particular significance, particularly around shamanistic transformation. Indeed, one elder described jaguars as representing shamanic knowledge, as though the animal has become an avatar. They also stressed the important of preserving the pictures, or risk severing the link between Indigenous people and their ancestors and traditions.

These efforts to include local communities have been supported by the creation of a diploma that will support sustainable cultural heritage tourism in the region.

“It is the first time that the views of Indigenous elders on their ancestors’ rock art have been fully incorporated into research in this part of the Amazon,” Dr Hampson said. “In so doing, it enables us to not simply look at the art from an outsiders’ perspective and guess; we know why specific motifs were painted, and what they mean. It enables us to understand that this is a sacred, ritualistic art, created within the framework of an animistic cosmology, in sacred places in the landscape. It also emphasizes how Indigenous belief systems and myths need to be taken seriously.

“I have worked with rock art and Indigenous groups on every continent – and never have we been fortunate enough to have such a direct fit between Indigenous testimony and specific rock art motifs.”