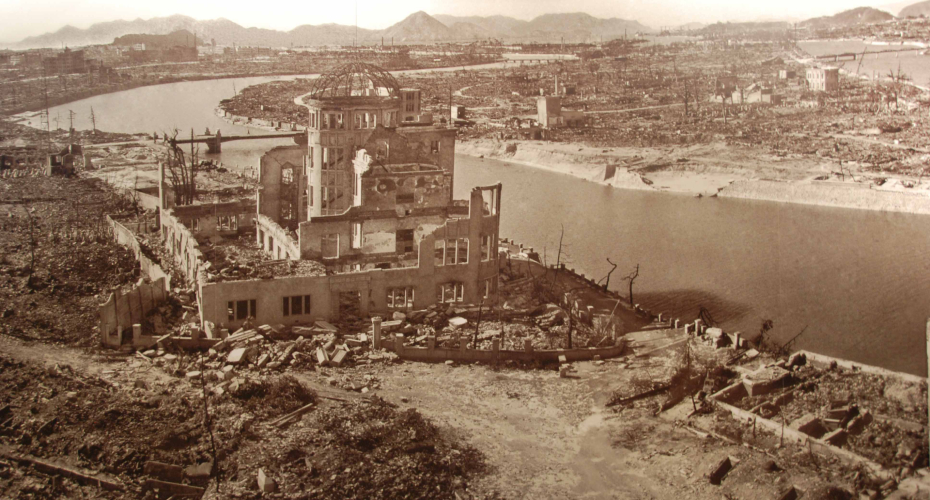

The 80th anniversary of Hiroshima

On the 80th anniversary of the dropping of the atomic bomb on the Japanese city of Hiroshima, historian Professor Richard Overy, a world-renowned authority on the Second World War, provides his perspective on the reasons behind it, and its figurative impact. Professor Overy’s book, Rain of Ruin, on this subject, was released this year.

For many years after the end of the Pacific War in August 1945, it has been assumed that the Japanese government and military leaders surrendered because of the two atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima on August 6 and on Nagasaki three days later. This remains the popular argument even today. The truth is more complex. The role of the two bombs in prompting surrender is open to question.

The Japanese emperor, Hirohito, and a cohort of senior advisers, both civilian and military, had been trying for at least six months before the bombs to find a way to terminate the war (the term surrender was never used) in the knowledge that Japan was facing defeat. There was growing fear among Japan’s elite that the home front might collapse as the Russian and German home fronts collapsed in 1917 and 1918. There was fear of a communist uprising if the war was not ended.

The home situation was made worse by the onset of a six-month incendiary bombing campaign by the United States Army Air Force, which burnt down 60 per cent of Japan’s urban area and forced ten million to flee to the villages and small towns, where they were difficult to feed and the possibility of social unrest more likely. The firebombing began with the catastrophic raid on Tokyo on the night of 9/10 March, in which at least 83,000 died. It continued until the day the emperor finally accepted the Allied ultimatum to abandon the war, which he did on 14 August.

The emperor by June had finally reached the conclusion that the Allied terms for unconditional surrender would have to be accepted as long as the imperial system could remain in place. But he and the ‘peace faction’ that supported him were faced with an army leadership that would rather fight a final – if hopeless – battle for the Japanese home islands than give in. The stalemate persisted over the summer until both sides agreed to try to get the Soviet Union, which was not yet at war with Japan, to intercede with the Western Allies to bring about an end to the war. It was a fantasy as the Soviet Union was about to declare war on Japan under the terms of agreement made with the United States and the British Empire earlier in the year. While Japanese leaders waited for a Soviet reply, the first bomb was dropped on Hiroshima.

The impact was limited because no one knew for sure what had happened. Many Japanese scientists refused to believe that any state could have made an atomic bomb in wartime. A commission of enquiry was sent, but the leading nuclear physicist in Japan did not arrive until 9 August, and a preliminary report reached Tokyo only on 10 August, after the emperor had already been asked to make a ‘sacred decision’ (a constitutional innovation) and had announced that the war had to be terminated.

The bomb on Nagasaki was hardly noticed because the same day the Red Army invaded Japan’s empire in northern China, dispelling any fantasy of Soviet intercession and raising the fear that Stalin’s army might reach and occupy Japan before the Americans. Fear of communism, together with the domestic crisis of food and evacuation, and the relentless firebombing, all played a more significant part in preparing the way to accept surrender and in the final decision. It took four more days of arguing over wording with the Americans before a final Imperial Conference was called on the morning of 14 August when Hirohito again spoke from the throne to say the ultimatum had to be accepted. Some army radicals tried to capture the imperial palace and prevent the Emperor’s radio broadcast to his people the following day, but on 15 August, at midday, the Japanese people heard their Emperor’s voice for the first time telling them that Japan was terminating the war. Formal surrender only occurred on 2 September after American occupation.

Stalin did not accept the Emperor’s announcement, and continued fighting the Japanese army to take all the territorial and security gains he had been promised by the other Allies. Red Army soldiers only completed their campaign on 5 September. Stalin wanted his soldiers to occupy northern Japan as well, but the American president, Harry Truman, refused and Stalin held back rather than prompt a military crisis. Though it has often been argued that the bomb was dropped to intimidate Stalin rather than force Japanese surrender, there is little evidence for this, while it had the opposite effect on Stalin, speeding up his territorial ambitions in East Asia rather than inhibiting them.

Japan’s surrender in the end owed much less to the bombs than is popularly believed. But the bombs were of great interest to the scientists and engineers who built them, and the soldiers who ordered their use. The use of the bomb was never seriously questioned by those who produced it, for they were curious to see what it would do after all their efforts if it was dropped on a city centre, as they recommended.

After the Japanese surrender, teams of scientists and engineers went to Japan from the United States and Britain to see what an atomic explosion did. They satisfied their curiosity, but not before over 200,000 Japanese and Korean civilians had been killed in the two brief August raids. It now seems likely that Japan would have surrendered in August, bombs or not, but using them before Japan surrendered became a priority for all those involved in producing them.