The Mystery of Diatom Movement Uncovered in New Study

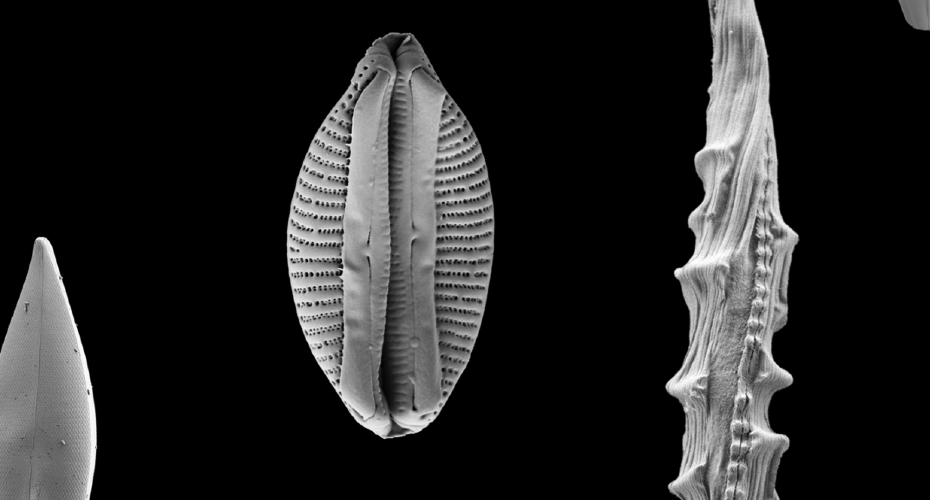

Microscope image of Diatoms. Image by Kirsty Wan

Researchers at the University of Exeter have discovered the secret behind the movement of diatoms, tiny single-celled algae that play a crucial role in aquatic ecosystems.

How these diatoms move was poorly understood, as they lack the appendages or cell flexibility that is usually required. Now a team of researchers, led by Professor Kirsty Wan from the University of Exeter’s Living Systems Institute, found that the unique shape of a specialised slit called the raphe is responsible for their gliding movement.

The shape of these raphe varies greatly among different diatom species, and this diversity affects how they move and interact with their environment. Diatoms can actively manipulate this gliding movement to spread across surfaces and form biofilms, which is essential for their survival and function.

The research, funded by the European Research Council (ERC) and UK research and innovation (UKRI), integrated precise experimental measurements of diatom gliding in 2D and 3D with realistic computer simulations. This method allowed the team to understand and predict how movement patterns of the diatoms influence their global, long-term dispersal.

Published in PNAS, this discovery has important consequences for how different diatom species distribute within complex multi-species ecosystems, and helps researchers understand how diatoms migrate towards nutrients and pheromones and regulate their light exposure.

As photosynthetic algae diatoms are at the bottom of marine food chains and are responsible for generating one-fifth of the world’s oxygen, making them extremely important to aquatic ecosystems and the ocean’s carbon cycle.

Kirsty Wan, the senior author of the study, said: “Diatoms are mysterious because they move by gliding on surfaces, even though they are basically made of glass and have no moving parts. Their movement, or motility, is a vital component of their normal physiology. Now that we have a more fundamental understanding of how cell shape constrains gliding function, we are poised to learn much more about how diatoms and diverse algae optimise their exposure to light and resources in naturalistic environments. These insights could inform future studies on improving photosynthesis in other organisms and also understanding the impact of climate change on these processes.”