Nearly £5 million from Wellcome to improve type 2 diabetes diagnosis in diverse populations

New funding of nearly £5 million will help researchers understand and develop better blood tests to diagnose type 2 diabetes, making them more accurate for groups including ethnic minorities and the elderly.

Wellcome has granted a team at the University of Exeter and Queen Mary University of London £4.9 million for an eight year project to understand an individual’s blood sugar – or glucose – levels more accurately. The findings will make the diagnosis and monitoring of type 2 diabetes more precise, ensuring people who need it get the best possible care and treatment.

An estimated five million people live with diabetes in the UK alone, and people from south Asian and African-Caribbean backgrounds are disproportionately affected. Getting a prompt and accurate diagnosis is crucial to starting appropriate treatment. This helps avoid the risks of life-threatening complications associated with high levels of glucose in the blood.

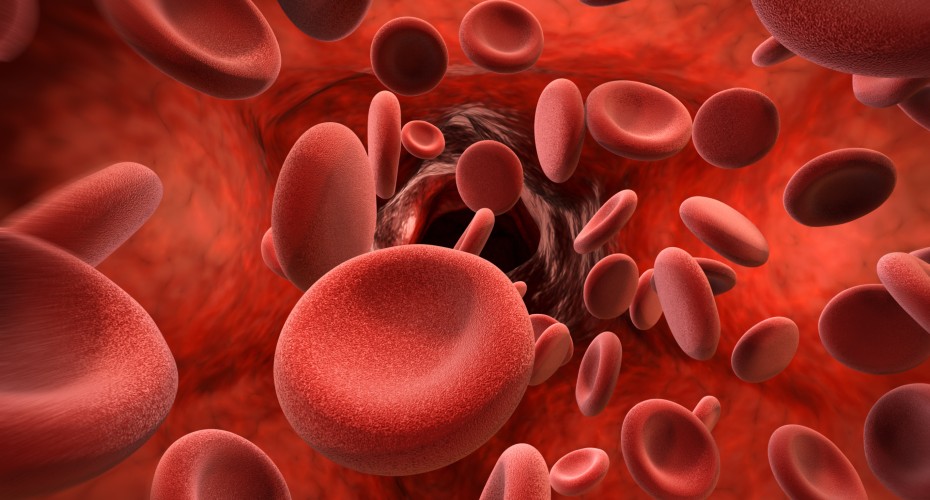

In the UK and many parts of the world, the routine test to diagnose and monitor type 2 diabetes is a blood test called glycated haemoglobin, or HbA1c. The HbA1c test measures how much glucose is attached to haemoglobin, the oxygen-carrying protein in red blood cells. The level of HbA1c is affected by a person’s average blood glucose, and how long their red blood cells live before they are replaced by the body. However, there are many factors that affect the HbA1c level that are not related to blood glucose. These factors include anaemia, a person’s age or ethnicity, and genetic factors.

Professor Inês Barroso, of the University of Exeter, the project lead, said: “Our team’s work has shown that there are specific DNA changes which are particularly prominent in people of South Asian and African-Caribbean origin that affect the accuracy of HbA1c. This finding is important as it might mean that using the same level of HbA1c to detect diabetes for everyone could lead to some people from ethnic minorities being under-diagnosed. Other research suggests it might lead to over-diagnosis of diabetes in elderly people.”

Professor Sarah Finer, lead from Queen Mary University of London, said: “Our research will help understand how many people are affected by these inaccuracies and make the diagnosis and monitoring of diabetes more reliable. This is crucial for the delivery of high quality clinical care of all people at risk of, and living with, type 2 diabetes.”

The team will invite participants of different age, sex and ethnicity to the study so they can understand how individual characteristics and genetic factors may alter HbA1c. They will also work in partnership with Genes & Health, and leverage studies such as the UK Biobank and the NIHR Bioresource, to build a large study that represents the diversity of the UK population.

Dr Veline L’Esperance, a GP and primary care lead for the project, said: “This project recognises the urgent need to improve health across the UK population, and in ethnic minority groups who are underrepresented in research. Our work will engage diverse communities in the UK to ensure our scientific discoveries can bring equitable health benefits to all.”