D-Day 80th anniversary: A Second Front at Last?

Operations Greenwood and Pomegranate Normandy July 1944 EN.svg: Philg88Derivative work: Hogweard, CC BY 4.0

In the week of the 80th anniversary of the D-Day landings, academics from across the Faculty of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences are providing a series of perspectives from their own disciplinary viewpoint.

To open the series, renowned historian Professor Richard Overy, author of books including Blood and Ruins and Russia’s War, frames the landings in the context of Russia’s demand for a second front in the theatre of war.

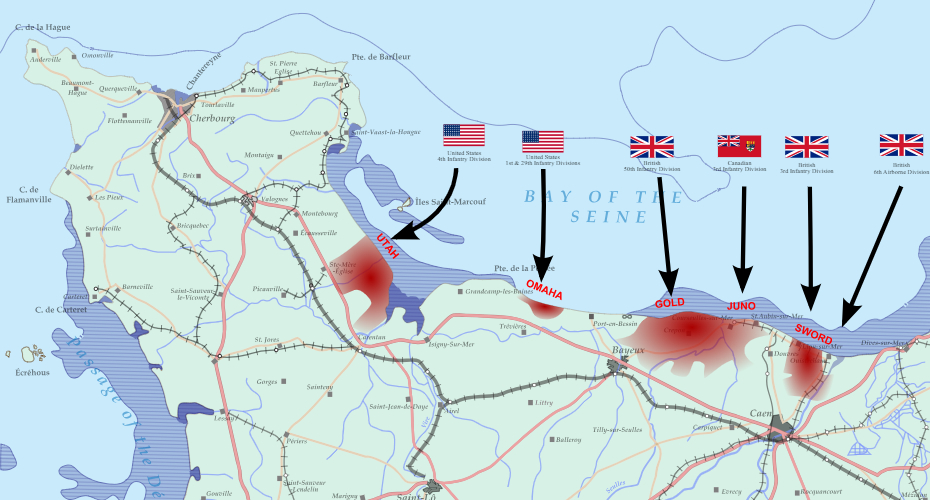

The invasion of Normandy on 6 June 1944, conventionally known as D-Day, was intended to open the ‘Second Front’ that Soviet leader Joseph Stalin had been demanding of his Western Allies since 1941. Vague promises were made in 1942 by American President Franklin Roosevelt, and repeated in 1943. The British Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, was far from enthusiastic and tried to persuade Stalin that the RAF bombing campaign against Germany virtually amounted to a Second Front by diverting German military resources to the defence of the Reich. He hoped that Stalin would also see the invasion of Sicily and Italy in summer 1943 as, in effect, another front.

Stalin was unimpressed. For him a ‘Second Front’ meant launching large armies at German-occupied Western Europe to draw German forces away from the Eastern Front. He did not believe in half measures. The relentless Red Army battering of the German army brought a terrible cost in death and destruction – almost nine million dead Soviet soldiers and airmen. Why did the Western Allies take so long to fulfil their assurances to their Soviet ally? In the first place, they wanted to avoid any risk of failure. Theirs was not a ground war, but a vast amphibious invasion. Defeat would mean both political and military humiliation and a second invasion attempt would not be possible before 1945 (by which time the Red Army might already have reached Berlin). Secondly, British, American, and Canadian troops were inexperienced and their commanders did not want to throw them into the cauldron of a major amphibious invasion until training and equipment were complete.

Above all, it proved difficult to reconcile strategic differences between the British and Americans. Churchill was consistently pessimistic about the prospects for an amphibious invasion, perhaps from memories of the failed attempt at Gallipoli in 1915, for which he was responsible. He favoured a Mediterranean strategy that would attack the weakest part of German-dominated Europe, knock Italy out of the war, and possibly open the way to an invasion of Germany from the south. Roosevelt’s military advisers were resolutely opposed to this strategic trajectory, to the extent that they might have turned to a ‘Japan first’ strategy if the British had proved difficult. In the end, Churchill had to follow his own commanders’ lead, who favoured a collaborative invasion carried out together with American and Canadian forces. It seems unlikely that Churchill could really have obstructed the launching of the ‘Second Front’, but he grumbled about it right up to the point of invasion. The American success in getting priority for OVERLORD, the campaign that began with D-Day, marked the point when the initiative in the war passed to the United States from the British Empire.

Even then, the condition for making D-Day possible was the success in deceiving the German armed forces about the primary objective in summer 1944. Deception was elaborate, and the purpose was to persuade the German side that the north-east of France, nearest to southern England, was the main invasion site. Any threat to Normandy, if it was discovered, would be presented as a decoy attack, designed to draw German forces away from the main locus of the campaign. The deception could so easily have gone wrong, but it succeeded only because Hitler and the German High Command assumed that the enemy would attack north-east France as the quickest route into Germany and the Ruhr industrial district; the possible threat to Normandy was indeed viewed by the German side as a deliberate and subsidiary diversion. The deception reinforced German perceptions. The bulk of German forces and armour were in the north-east, the Normandy front more weakly held.

It is easy to understand Stalin’s impatience. Indeed, by the time of D-Day, Stalin had decided that the Red Army could probably win the war against Germany on its own. The huge ground battle in Belorussia, begun on 21/22 June, Operation Bagration, was immediately successful and the Soviet side contrasted the rapid advance of the Red Army with the slow slugging match in the Normandy countryside after D-Day. Perhaps the Red Army could have done it alone (though helped by heavy Anglo-American bombing and Lend-Lease aid), but, as the Americans realised, a ‘Second Front’ was essential politically as well as militarily. Failure to attack in the West would send the wrong message to the peoples of occupied Western Europe, encourage the further spread of communism, and undermine the Grand Alliance at a critical stage in the Allied war effort.

Churchill had been right to worry about the invasion – which took weeks of effort before it bore fruit – but wrong about Western strategy. The ‘Second Front’ was a necessary one. The troops who waded ashore under heavy fire on the morning of 6 June were doing more than fighting the Germans. They were opening the prospect of a revived and democratic Western Europe, free of German domination and able to confront any possible Soviet threat.