D-Day 80th Anniversary: Germany’s cultural response to Normandy

In the week of the 80th anniversary of the D-Day landings, academics from across the Faculty of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences are providing a series of perspectives from their own disciplinary viewpoint. The second piece has been written by Professor Chloe Paver, Associate Professor in German, who looks at the culture of remembrance in Germany and its complicated relationship with Normandy.

The 80th anniversary of D-Day, while a major event in France and the UK, promises to pass quietly in Germany. As an expert in German history museums I keep an eye out for upcoming exhibitions. To date, no museum has announced an exhibition about D-Day, though exhibitions this year will mark the 75th anniversary of the Berlin Air Lift and of the German Constitution. German cultural responses to the Normandy commemorations seem likely to be limited to media commentary.

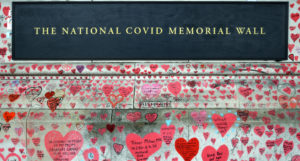

This reticence is not a sign that Germany has swept its past under the carpet. On the contrary. Two new museums – one about Nazi slave labour, one about the Nazi occupation of Europe – will soon take their place among the several dozen museums and education sites that have been founded in the past 20 years to reflect on the Nazi dictatorship. Is the UK opening one museum per year to reflect on colonialism and slavery? No.

Nor is it a sign that Germany lacks the anniversary reflex. Quite the reverse. Because the National Socialist era lasted for longer than ten years, every year in the decade is potentially an anniversary year, with the threes, fives, and eights particularly busy with anniversary exhibitions, ceremonies, and symposia.

Why, then, are the Normandy landings less prominent in German memory?

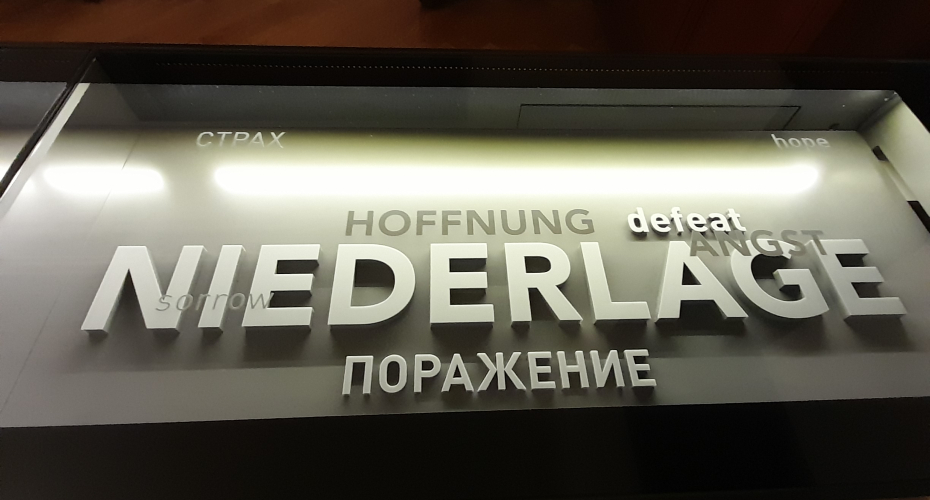

In 1985, the then Bundespräsident, Richard von Weizsäcker, was the first major politician to insist that Germany had not been defeated but liberated in 1945. In a speech to mark the 40th anniversary of the end of the war he stated that 8th May 1945 ‘hat uns alle befreit von dem menschenverachtenden System der nationalsozialistischen Gewaltherrschaft’ (‘freed us all from the inhumane system that was the Nazi dictatorship’).

While the Weizsäcker speech could not alter ordinary Germans’ felt experience of pain, loss, and bereavement in 1945, it created a new framework for the public understanding of the past and it helped fix the date 8th May 1945 in public memory. By contrast, the 6th June 1944 has little hold in the German imagination. Moreover, notwithstanding Weizsäcker’s speech, the word ‘Befreiung’ (liberation) is still more likely to be used in connection with the liberation of the concentration camps than with the liberation of the German people, whatever date is chosen for the beginning of that process.

Another reason why the D-Day landings do not readily fit into available formats for German remembrance is localism. Memory of Nazi crimes, of state terror and discrimination – and also of the Jewish lives that thrived before the persecution began – has been driven by local energies. And since, unlike much of Britain’s involvement in slavery and colonization, National Socialism happened in Germany itself, local historical research has been replicated nationwide: What happened to our Jewish neighbours? Which of our factories or farms had slave labourers? What involvement did our hospital or university have in National Socialism? Accordingly, over the last few years many towns have commemorated 80 years since the Jews or Roma of their town were deported. This year, some are commemorating 80 years since a night of Allied bombing or 80 years since a local opponent of Nazism was executed in the last cruel months of judicial repression.

I see this localism positively, as a potent machine for generating research and reflection, but it is a machine that is hard to feed with events such as the Normandy landings that happened a long way away, outside the borders of Germany, especially since they are unlikely to have involved more than one or maybe two soldiers from any given locality. This is equally true of the Battle of Stalingrad, which is addressed in national museums rather than local exhibitions. Occasionally, the local and international meet in an exceptional case: a delegation recently travelled from Erlangen to a village in Italy where, 80 years ago, an Erlangen SS man ordered a massacre of Italian villagers.

When I was first invited to write this piece, I did what all good scholars do: I googled the topic. The first hit was a page from a Normandy campsite, encouraging German visitors to book a pitch for the commemorations: ‘Sie können diesen historischen Moment voll und ganz genießen, indem Sie im Juni 2024 auf Castel Camping du Brévedent übernachten’ (‘You can enjoy this historic moment to the full by staying at Castel Camping in Brévedent in June 2024’). As I have one foot in Translation Studies, I am interested in what happens when text is translated automatically ‒ not by translation software, but according to a company policy that requires each French page to have an equivalent German page. In another campsite advert, the German soldiers who fought in Normandy appear only obliquely in the words ‘feindliche Kugeln’ (‘enemy bullets’), dutifully translated from the original French. German tourists are a big customer group for campsites in Normandy, but will they be attracted by a rhetoric that addresses a different demographic?

Germany’s relationship with present-day Normandy is complicated not just by regular tourism but by the fact that there are German war cemeteries there, maintained by the German war graves association, the VDK. German families still visit the graves, as I know because I visited one with my father and we saw fresh wreaths. My dad, who had personal reasons for hating Nazi Germany, since his father died from an illness contracted in a POW camp in Thuringia, was moved by this display and was reminded of everybody’s right to mourn their dead.

Some of the re-enactments that are a staple of D-Day commemorations in Normandy will still need their ‘Germans’ to make the spectacle work, and German politicians will travel to Normandy this June to make speeches about peace in Europe and war in Ukraine, but back in Germany, centrist Germans will get on with their decades-long task of remembering other anniversaries in other ways, albeit in the same pursuit of stable democratic values.