Exeter students burst bubble-making world record

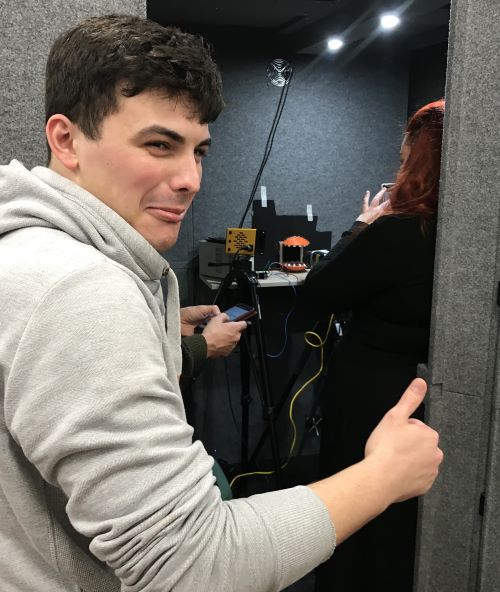

The student bubble-makers' elaborate set-up, including an acoustic levitator (centre, in orange)

Two University of Exeter physics students believe they have broken the world record for making the longest lasting bubble.

Third-year students Boden Duffy and Joe Nightingale managed to form a bubble and keep it in the air for 1 hour 24 mins, beating the world record by over an hour.

The record attempt was made on Monday in a soundproof room in the Physics laboratory at the University of Exeter.

A group of witnesses watched the hour-long attempt, and video footage will now be sent to the Guinness Book of World Records for official verification.

The record was specifically for the longest-lasting bubble made using an acoustic levitation machine, a device that uses acoustic radiation pressure from high intensity sound waves suspending matter in air against gravity.

Each bubble, which is only a couple of millimetres in diameter, is formed by a round droplet of water in a soapy solution, which is flattened by acoustic pressure into a disk of water before being curled up to form a bubble.

Formation only takes a couple of milliseconds, with the process captured using a high-speed camera, and as one machine forms the bubble, another keeps it perfectly still in the air.

“We found that a lot of people have used the acoustic levitator to study droplets but not the bubbles it can create,” said Joe.

“We’ve based our project on some of those research papers we’ve found. We’re trying to replicate some of those experiments with bubbles to see if we can get the same results or find something new.”

The students said were very confident before making the attempt and in the event, after watching the bubble for over an hour, decided to burst it themselves so they could “move on with their lives”.

The students’ record-making ambitions evolved from their final year project studying the oscillation modes of bubbles.

They quickly realised that they were quite good at making the bubbles, and that the bubbles were lasting for a long time.

“Once we’d formed a bubble, it just sort of happened,” said Boden, describing the process. “The hardest part is probably setting it all up,” added Joe.

Bubble-making may not be a feasible career option but, as Dr Chris Brunt explains, there are plenty of practical applications for acoustic levitators.

“They’re useful in many fields, used in manufacturing microchips as well as scientific research where small insects, cells or droplets can be levitated under a microscope for observation.

They provide a sterile environment and eliminate the risk of damaging fragile objects. They also allow scientists to perform touchless chemical reactions where two different substances never come in contact with any surface except each other.” he said.