Specialist laboratory exploring experimental techniques to improve the resolution of analyses on the felled Sycamore Gap tree

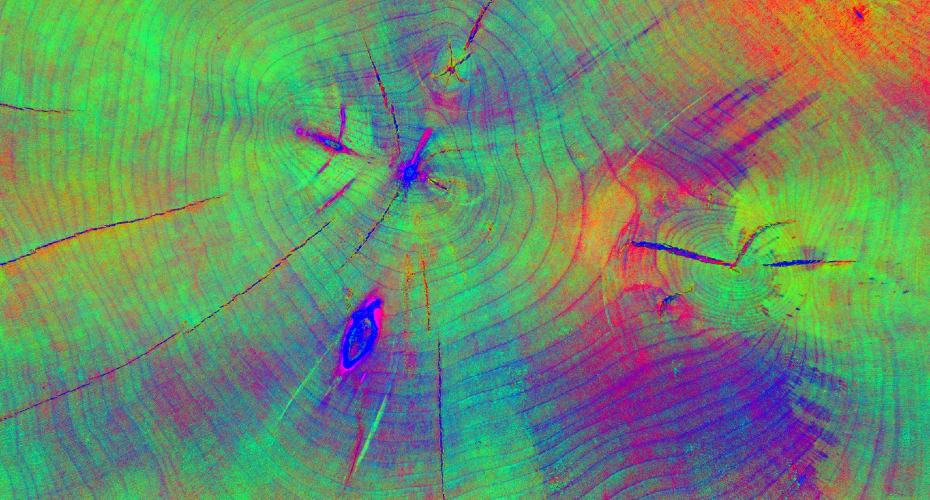

Decorrelation Stretch applied to the photogrammetry-derived orthomosaic of the tree slice

A university laboratory specialising in digital preservation and the digital display of historic artefacts is playing a key role in efforts to commemorate the felled Sycamore Gap tree.

The Digital Humanities Lab at the University of Exeter is exploring computer vision and imaging techniques on a slice of the tree to assist Historic England in more accurately dating its age.

Specialists in the team have produced an array of models of the wood’s surface and structure to make it easier to see the growth rings, which are used to calculate a tree’s age.

The Digital Humanities Lab team also hopes that the ultra-high-definition models produced through the project might form the basis for future interactive 3D representations of the tree.

Earlier this month, Historic England revealed that the Sycamore, which was a prominent feature in the Hadrian’s Wall landscape in Northumberland, was at least 100 to 120 years when it was illegally felled, and probably appeared in the landscape in the late 19th century or earlier.

“By employing digital visualisation techniques including photogrammetry and Reflectance Transformation Imaging (RTI), we have been able to capture the Sycamore Gap specimen in incredible detail,” said Dr Adrián Oyaneder, an archaeologist at the University and member of the project team. “This is intended to help Historic England refine their age calculations and could potentially shape how we publicly memorialise the tree in the future.”

The collaboration was inspired by an event organised by the University’s Heritage@Exeter network, which brings together academics and heritage organisations to discuss potential projects. With funding provided by the network, Dr Oyaneder and the team from the laboratory – Graham Fereday, Research IT Officer; and Julia Hopkin (now a PhD candidate at Glasgow) – travelled to Fort Cumberland Laboratories in Portsmouth, where a cross-section of the tree has been stored.

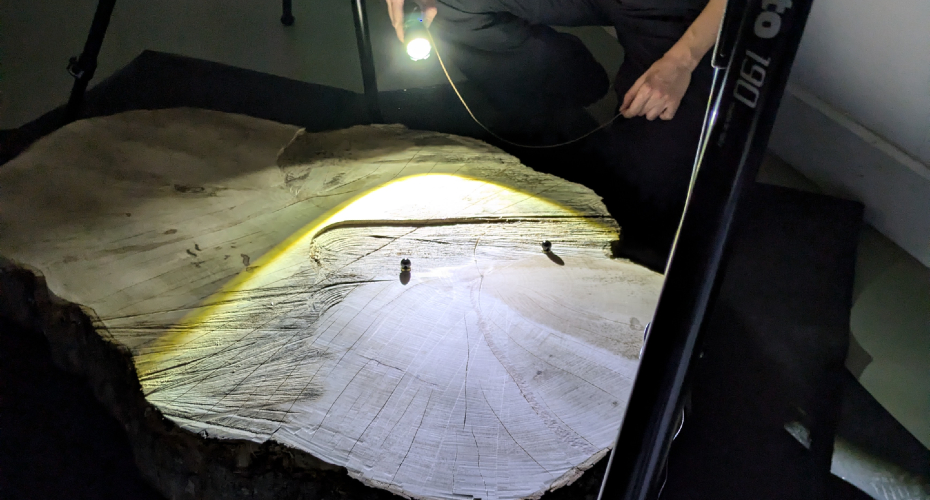

Over the course of a day, they utilised numerous techniques to create different visualisations of the tree slice. This included close-range photogrammetry, which involves the taking of multiple images from different angles to create high-resolution ‘mosaics’ of the object.

The team also used RTI, which employs an array of light sources around the object that can be later manipulated and enhanced in-software, revealing hidden details as the angle of the light is changed. It also enables the surface texture to be analysed in detail, exaggerating or highlighting key features of the subject, creating a ‘2.5D’ view of the tree’s rings as a digital representation, potentially allowing the public to see their structure.

Historic England’s Investigative Science Team will assess whether this imagery can provide further information about the tree’s age. This work is being led by Gill Campbell, Head of Fort Cumberland Laboratories, along with Cathy Tyers, Dendrochronologist; and Dr Zoë Hazell, Senior Palaeoecologist.

Since the illegal felling, Historic England, the National Trust and Northumberland National Park Authority have worked together to create a series of initiatives designed to mark the legacy of the tree and engage communities at a local and national level.

“I am really enjoying working with Dr Oyaneder and the Digital Humanities lab on this project,” said Gill Campbell. “I am looking forward to sharing the images with the public and what analysis of the images can tell us about the life history of this iconic tree.”

“This might sound like a cliché, but it was an honour to work on this project,” adds Dr Oyaneder. “This act of desecration caused public outcry, so it is great to be contributing to a project that preserves the biography of the tree and might create new interactive representations for the public. It might also enable scientists to learn something of the climate during the tree’s different historic growing seasons.”

The Digital Humanities Lab opened in 2017 as a research and teaching space for the University on its Streatham campus, and has been working with numerous heritage organisations, often in conjunction with the Societies and Cultures Institute and the Heritage@Exeter network.

“The ethos of the Digital Humanities Lab is about taking something familiar that we know and think we understand, to reveal new elements or aspects of it,” adds Gary Stringer, Head of Digital Humanities. “It’s enhancing what is already there, giving greater understanding, but doing so in a non-invasive, non-destructive manner.

“We believe there is great potential in employing some of the more ‘forensic’ techniques commonly associated with science to a heritage application. That is reflected in the appetite of those cultural and heritage organisations who are looking to partner with us on projects that preserve or re-present artefacts from the past for contemporary audiences.”

For more information on the Digital Humanities Laboratory, visit the University of Exeter website.