Engineered moths could replace mice in research into “one of the biggest threats to human health”

A scientific breakthrough not only promises faster testing for antimicrobial resistance, but also an ethical solution to the controversial issue of using rodents in research.

University of Exeter scientists have created the world’s first genetically engineered wax moths – a development which could both accelerate the fight against antimicrobial resistance (AMR) and significantly reduce the need for mice and rats in infection research.

The study, published in Nature Lab Animal, outlines how Exeter researchers have developed powerful new genetic tools for the greater wax moth (Galleria Mellonella). This small insect is increasingly recognised as a cost-effective, ethically sustainable alternative to mammals.

Dr James Pearce from the University of Exeter said: “With AMR posing one of the biggest threats to human health, we urgently need faster, ethical, and scalable ways to test new research. Engineered wax moths offer exactly that – a practical alternative that reduces mammalian use and accelerates knowledge discovery.”

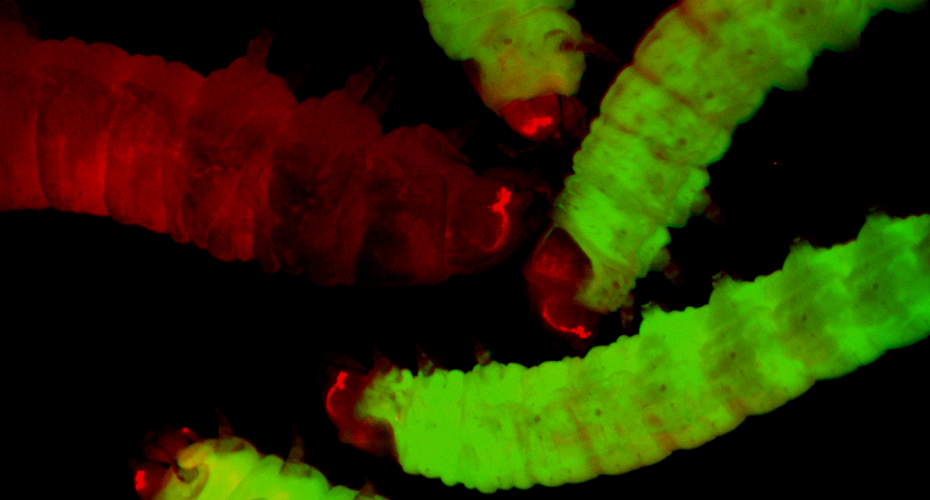

Unlike most other non-rodent model organisms, the greater wax moth can be reared at 37 degrees Celsius – human body temperature – and the response of its cells to bacterial or fungal infection closely mirrors that of mammals. Yet, until now, its use as a model organism has been limited by the lack of genetic tools. Exeter researchers have overcome this by adapting technologies originally developed for fruit fly research, to create fluorescent transgenic and gene edited moth lines for the first time.

Professor James Wakefield from the University of Exeter said: “By putting new genes into the wax moth genome, we’re able to make larvae that glow in a controlled way. This paves the way for ‘sensor moths’ that light up when infected or responding to antibiotics – offering a living, real-time window into disease.”

Sensor moths could transform early-stage infection studies, enabling rapid antimicrobial screening and immune response analysis in a whole organism, without the need for mice or rats. The larvae respond to human pathogens such as the superbug Staphylococcus aureus or the opportunistic fungus, Candida albicans, and therefore provide a realistic yet ethical bridge between cell culture and animal testing.

Dr James Pearce continued: “Our methods make wax moths genetically tractable for the first time. The ability to insert, delete or modify genes opens huge potential, from understanding innate immunity to developing real-time biosensors for infection.”

The impact on the use of animals for scientific experimentation could be substantial. Each year, around 100,000 mice are used in the UK for infection biology research. If only 10 per cent of those studies were replaced with moths, over 10,000 mice annually could be spared – while still generating robust, human-relevant data.

This research builds on over five years of investment from the National Centre for the Replacement, Refinement and Reduction of Animals in Research, alongside collaboration and funding from the Defence Science and Technology Laboratory, and the University of Exeter’s advanced imaging and genomics facilities.

The Exeter team have made all methods openly available through the Galleria Mellonella Research Centre, which they co-direct. The Centre now supports more than 20 research groups worldwide with training, wax moths and data resources, standardising and accelerating global adoption of this powerful model organism.

The paper titled ‘PiggyBac mediated transgenesis and CRISPR/Cas9 knockout in the greater waxmoth, Galleria mellonella’ is published in Nature Lab Animal.