Continental shelf seas revealed as powerful carbon sinks, but cutting global emissions remains critical to safeguard sea life

Continental shelf seas – the shallow waters surrounding our coasts that provide most of the world’s seafood – are absorbing more carbon than they release, with the strength and direction of the prevailing wind proving a key control, new research shows.

This may sound like good news for slowing climate change, but scientists warn it comes at a cost: rising ocean acidification that threatens marine life and global food security.

The new study, led by researchers with the Convex Seascape Survey, is the first to provide observation-based evidence that the movement of water on and off continental shelves plays a major role in how much carbon these seas retain.

By analysing 20 years of data from 14 shelf seas worldwide, the scientists found that carbon uptake and release is controlled by seasonal wind-driven currents at the shelf edge – the point at which shallow seas meet the open ocean. These currents and their flows act like a highway, transporting carbon onto or off the shelf into the deep ocean, with net transport dependent on wind direction.

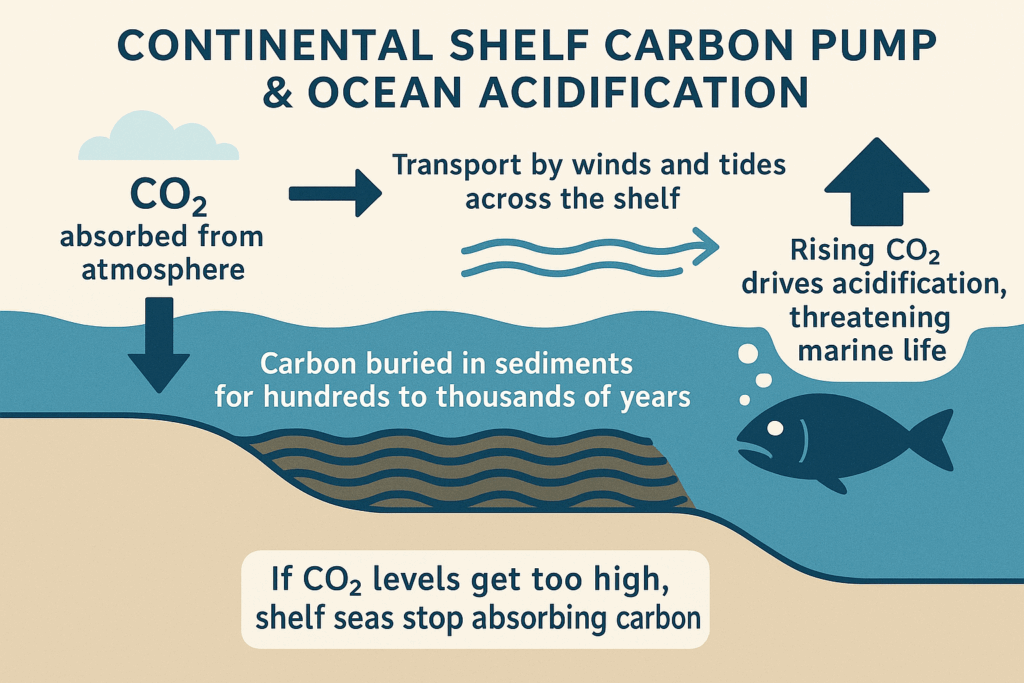

This is the first time scientists have been able to quantify the global importance of these current-driven exchanges, providing new insight into the mechanics of this process, which is often called the “continental shelf sea carbon pump”.

“Continental shelf seas act like giant sponges, helping to draw carbon down from the atmosphere, into the water. The shelves then move the carbon into the deep ocean where it could remain for hundreds or thousands of years,” said Professor Jamie Shutler from the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences at the University of Exeter, who led the study.

“But while this carbon uptake has so far helped to reduce the climate impacts we experience on land, it also drives ocean acidification as dissolved CO2 forms a weak acid. This isn’t good news for plankton, fish and coastal bivalves like mussels and oysters, as their habitats are shrinking. We get more than 90% of our seafood from these seas, so it’s also a serious food security issue.”

Cutting emissions remains critical

The findings highlight a double-edged sword: while strong shelf-edge currents may allow shelf seas to continue absorbing atmospheric carbon, this absorption comes with increasing risks of acidification. Crucially, the main driver of carbon uptake is the rising carbon emissions generated from human activities and lifestyles, including our desire for new technology.

“This study refines our understanding of how the ocean works,” said Professor Callum Roberts, another author of the study and lead scientist of the Convex Seascape Survey. “At the same time, it reinforces the bottom line: drastically reducing emissions is the single most important action we can take for the health of our seas.”

“Cutting emissions remains the only way to keep our seafood safe for future generations. Without that, all our other important global efforts, such as the creation of marine protected areas, will be fighting a losing battle.”

The Convex Seascape Survey is a partnership between Blue Marine Foundation, the University of Exeter, and Convex Group Limited. The ambitious five-year global research programme is the largest attempt yet to build a greater understanding of the properties and capabilities of the ocean and its continental shelves in the Earth’s carbon cycle, and how these seas are being impacted by human activities.

The paper, published in the journal Global Biogeochemical Cycles, is entitled: “Wind-driven control of shelf-sea CO2 sinks.”

The work is a collaboration between the European Space Agency and the Convex Seascape Survey.