Automatically learning how to sort out light

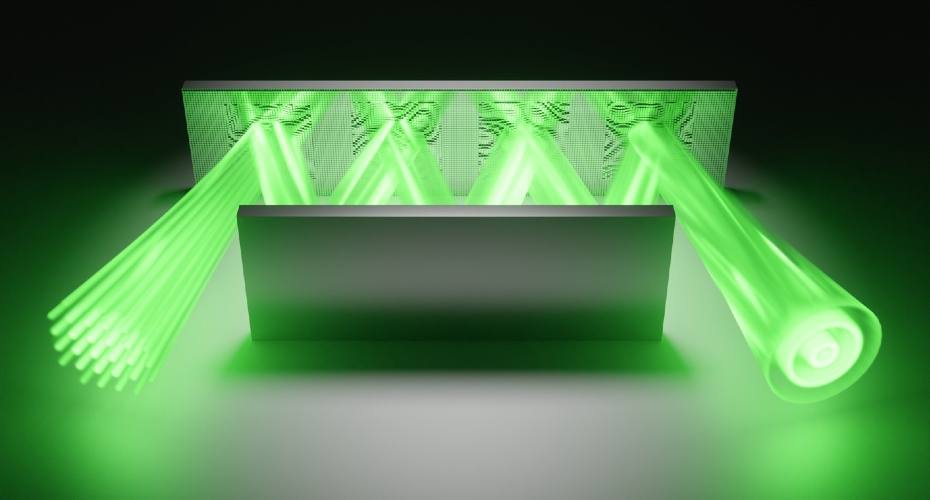

An incoming light beam strikes a newly developed high-speed phase-only light modulator, whose micrometre-scale mirrors piston vertically to impose a varying 2D delay to the reflected light. As light travels and reflects through multiple mirror height profiles, each reflection transformation builds upon the last, progressively reshaping light to produce an output beam with tailored properties. Image credit: José C. A. Rocha.

Light can be sculpted into countless shapes. Yet building optical devices that can simultaneously manipulate many different optical patterns at once is extremely complicated, and remains a major challenge in modern photonics.

But now a team of physicists from the University of Exeter and the University of Queensland, Australia have taken a key step forward by showing it is possible to teach light-controlling devices how to adaptively reorganise light beams themselves, mastering the enormous complexity of many thousands of degrees of freedom, without the need for human intervention.

Such adaptive control paves the way for an array of transformative applications, including unscrambling light to peer deep within biological tissue, vastly increasing the capacity of optical networks, and bringing closer emerging forms of optical computing. This concept also has the potential to act as a fundamental building block for future quantum systems.

The new research, published in Nature Communications, was led by Professor David Phillips and PhD student José Carlos A. Rocha, of the Structured Light Group within the Department of Physics and Astronomy.

“Light has many properties that scientists have found ways to control – such as colour, polarisation and the direction of propagation,” said Professor Phillips. “Precise control over these properties underpins much of modern technology – it is an essential hidden layer of many devices we rely on every day, such as the architecture of high-speed fibre optic internet. For example, light beams can be intricately patterned, allowing them to carry large amounts of information stored as images. As yet, this is a relatively untapped resource in communication systems, since it turns out to be the most difficult of light’s features to control precisely.”

“The shape of a beam of light, no matter how elaborate, can be thought of as a mixture of many simpler independent shapes,” adds Rocha. “Like trains running on parallel tracks, each of these underlying simpler shapes carries its own independent channel of information. In principle, these shapes can be separated or transformed into new ones, allowing the information they carry to be measured or processed in the optical domain, but achieving this when these shapes are all mixed together on top of one another in the same light beam is extremely challenging.

“The difficulty lies in the fact that when you try to address one shape, you inevitably disturb all the others at the same time. Separating and manipulating these shapes of light in a controlled way is a major goal of modern photonics, as it would enable the use these different tracks of information simultaneously – something that is not yet widely possible.”

This is where an emerging technology known as multi-plane light conversion plays a crucial role, say the researchers. Multiplane light converters (MPLCs) – which are also known as diffractive neural networks – break down the challenge of manipulating the spatial shape of light beams into a series of simpler steps.

An MPLC is a specially shaped cavity through which light bounces. The light beam is repeatedly imprinted with a carefully designed set of patterns. Each of these reflections nudges the beam closer to its final desired shape, so that after the final reflection, the shape of the beam has been transformed as required.

In this way, MPLCs can efficiently process many different light shapes in parallel, offering an unprecedented level of control over the information carried by the light beam. MPLCs already sit at the core of emerging photonic technologies, from high-capacity optical communication links to advanced forms of imaging. However, a key limitation has stalled the wider use of MPLCs: they are extremely difficult to build.

Traditionally, an MPLC is first designed using a detailed digital model of the optical system – all distances, sizes, angles must be known with incredibly high precision, constituting many thousands of degrees of freedom. When implemented in the real world, even tiny fabrication errors quickly snowball and result in the transformation quality degrading dramatically. Such is the challenge, that only a handful of laboratories worldwide can reliably construct such devices. Furthermore, another constraint of conventional MPLCs is that their desired operation is often fixed at the time of construction and cannot be changed thereafter.

To overcome these challenges, the Exeter-Queensland team developed a new fast-switching MPLC platform based on a tuneable micro-mirror array: a grid of roughly one million reconfigurable piston-action micrometer scale mirrors that can be adjusted over 1,000 times a second to imprint tuneable patterns onto reflected light.

Taking advantage of the unprecedented switching speed of this high-speed MPLC, the team programmed it to automatically learn how to configure itself, precisely tuning the heights of these micro-mirrors to accurately achieve any desired linear light processing function. This new approach represents a significant step forward in the development of MPLC technologies, pushing the limits in complexity of light processing possible, and paving the way towards a new set of ultra-high fidelity light shaping tools.

“Because our system learns directly from the physical experiment, it naturally adapts to the task at hand”, says Rocha, first author of the study. “This makes multi-plane light converters far more practical for real-world technologies, especially in scenarios where the required transformation may need to change over time.”

The research was supported by the European Research Council, the UK Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, and the Australian Research Council. José Carlos Rocha was supported by the QUEX Institute, a joint initiative between The University of Queensland and the University of Exeter, tackling ambitious projects in the spheres of disruptive digital technology and global challenges.

The article Self-configuring high-speed multi-plane light conversion, by José Carlos A. Rocha, Unė G. Būtaitė, Joel Carpenter and David B. Phillips, has been published in Nature Communications.