Red Hand Day 2025: Historical Perspectives on Child Soldiers

Written by Professor Stacey Hynd and Dr Chessie Baldwin, from the Department of Archaeology and History.

Red Hand Day - Kinder sind keine Soldaten, public access via Wikimedia Commons

Between 2005 and 2022, more than 105,000 children are estimated to have been recruited and used in armed conflict around the world. Today, under-eighteens are involved in contemporary conflicts in Ukraine, Palestine, Syria, Ethiopia and elsewhere, navigating global norms of adulthood as they collide with local realities of militarism, resistance and survival.

Every year on 12 February, advocates and policymakers mark Red Hand Day to call for the end of child soldiering. Red Hand Day, or the International Day against the Use of Child Soldiers was inaugurated in 2002 by the Coalition to Stop the Use of Child Soldiers. More than 450,000 handprints have been collected in over 50 countries to protest children’s military recruitment and use.

As historians of child soldiers in Africa since 1940, we are reflecting on the roots of this practice after this year’s annual campaign day, asking when, why and how children have been recruited to serve in armed groups, but also why the international community cares about this issue at some points in time more than others.

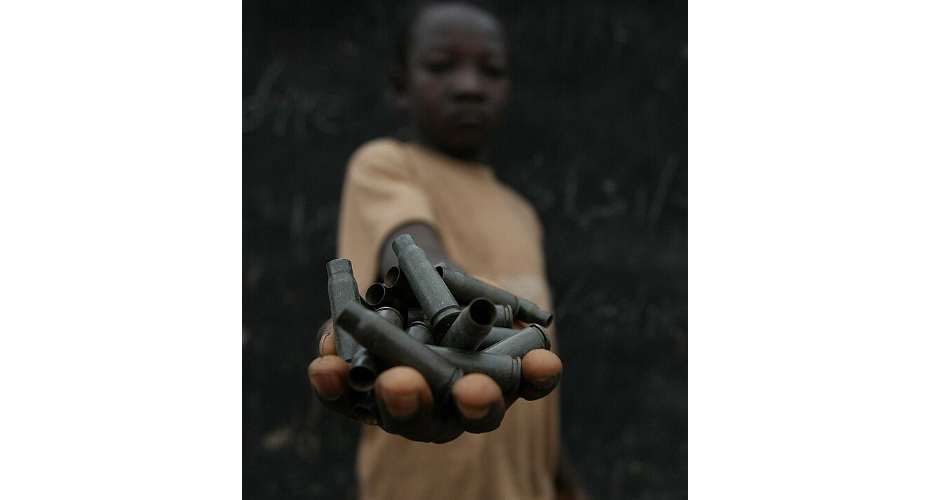

The issue of child soldiering exploded onto the international agenda in the 1990s, iconically represented by the figure of a small African boy wielding an AK 47. Amidst a new era of child rights, humanitarian campaigning demanded the increased protection of children in war, fighting to raise the age of recruitment from 15 to 18 in the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child signed in 2000. But long before global media was dominated by pictures of armed children in the ‘hyper-violent, ‘new wars’ of the 1990s, children were present and active in armed groups: as soldiers, messengers, spies, informants, auxiliary workers, cooks, and much more. Their presence often went unremarked and was rarely contested, but they made significant contributions to war efforts, from the American civil war to the Second World War.

Fluid, divergent and locally defined categories of child, adolescent and youth haves shaped the question of who is and is not a ‘child’ and who is ready to be a ‘soldier’ throughout history, not least in Africa. In pre-colonial Sudan and Abyssinia, militancy was viewed as a key initiation experience to transition from boyhood to adulthood, regardless of biological age. Colonialism brought European military cultures – with their own traditions of child recruitment – into Africa, along with new colonial ideas of childhood, education and youth socialization. British colonial armies targeted schoolboys as skilled recruits, and many young African boys were recruited to fight overseas during the Second World War. During the 1950-80s decolonization era, teenagers – both boys and girls – played significant roles in anti-colonial liberation struggles, mobilized by the politization of childhood and youth in late-colonial governance, including in the fight against apartheid from the African National Congress.

The Cold War brought Communist traditions of child and youth militarization into Ethiopia and Angola, spurring children’s military recruitment. In Nigeria, starving Biafran infants became the dominant icons of the 1967-70 civil war and famine, but thousands of older children fought for Biafra’s survival, including serving as spies behind enemy lines. In our research, we argue that the ‘child soldier crisis’ emerged in late 1980-90s not because children suddenly appeared on global battlefields, but because changing notions of childhood, child rights, human security and war made them objects of humanitarian concern. Africa became a key locus of child soldier advocacy, driven by horrifying examples from wars in Sierra Leone, Liberia, Uganda and the Democratic Republic of Congo and underpinned by racialised and paternalistic notions of ‘the dark continent’.

In the mid-1990s to early 2010s, child soldiering was at the forefront of humanitarian concern, entering also into popular consciousness and culture, through memoirs from former child soldiers-turned-advocates, novels and films like Beasts of No Nation, as well as high-profile advocacy campaigns like Kony 2012. Humanitarian action achieved significant successes in persuading governments and armed groups across the globe to demobilize child combatants and stop under-age recruitment, and the recruitment of children under fifteen was declared a war crime by the International Criminal Court in 1998.

In recent years however the plight of child soldiers has slipped down humanitarian agendas and out of the public eye, as attention turned towards child suffering in other crises, from displacement and refugees in Latin America, to radicalization and exploitation by terrorist groups in the Middle East. The ‘Bring Back Our Girls’ campaign to rescue the 276 Chibok girls kidnapped by Boko Haram in 2014 was framed in terms of ‘girl-saving’ rather than as part of wider efforts to prevent the abduction and recruitment of children into armed groups. Child soldiering however is inextricably interlinked with these other forms of child exploitation in situations of armed conflict and violence. It remains a significant global challenge, and not just a Global South issue. The United Kingdom is one of only fifteen countries in the world that still allows the military enlistment of children aged 16.

Historical research helps to reveal the longer-term structural, cultural and political factors that shape both children’s military recruitment and responses to it from local and international communities, as well as its relationship to other forms of child labour exploitation and youth violence. As we turn our attention to mark 2025’s Red Hand Day, the daily experiences of violence and instability plaguing children and adults alike around the world reminds us of the historically contingent realities that affect children’s participation in armed conflict.