New book reveals the historical inspirations for cinemas, streaming services and reality TV

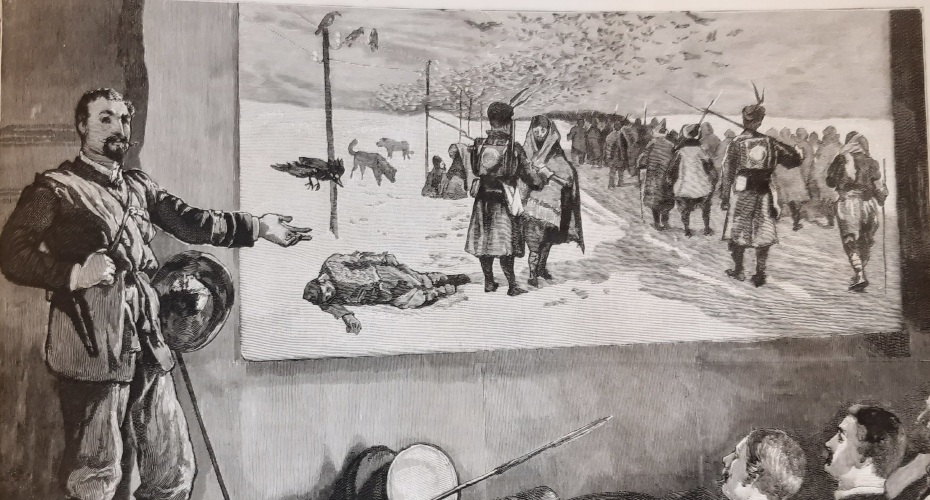

Depiction of magic lantern lecture by Federic Villiers, Special Artist of The Graphic (1887). Picture courtesy of the Bill Douglas Cinema Museum

The historical forerunners of IMAX, Netflix, and the PowerPoint presentation can be traced back to the 19th and early 20th century, according to a ground-breaking new book.

Magic lanterns, panoramas, stereoscopes, and camera obscuras all stimulated public appetite for moving and projected images, creating a picture-going industry that would ultimately pave the way for contemporary cinemas, streaming services and reality TV.

Written by experts at the University of Exeter, the book – Popular Visual Shows 1800–1914: Picturegoing from Peep Shows to Film – is based upon years of research into the period, and reveals how people embraced (and worried about) the pervasiveness of visual media two centuries before the advent of smartphones. Visual shows and media became a way for ordinary people to be entertained and to understand the changing world around them.

From the founding role of high street opticians who rented out visual entertainments like a proto form of Blockbuster, to priests and politicians – including Winston Churchill – who delivered sermons and campaigns using magic lantern slides, the book uncovers some of the hidden stories behind public appetite for mass visual media.

It has been written by a pair of experts at the University of Exeter – Joe Kember, a Professor in Film and Media; and Professor John Plunkett, Associate Professor of English and Creative Writing – and is based on their extensive research into the period.

“When you hear the term ‘picture-going’, people immediately think of the cinema,” says Professor Plunkett. “But picture-going became part of daily life for people in the 19th century, and it extended across multiple media – from painted panoramas, which were the IMAX of the era, to stereoscopes and its 3D images that were as immersive then as virtual reality is today.”

The book charts the emergence in the early 19th century of the first touring shows, where audiences would pay to see projected images or panoramas depicting the latest national event or offering virtual travel to overseas countries. Over time, networks of touring lecturers and speakers were established, with transparencies and magic lanterns used to display election results and other important information.

Professor Kember said that such visual media proliferated well beyond the world of entertainment, and were regularly used by schools, colleges and churches.

“Clergymen would often use magic lanterns as part of their sermon or at the end of a Sunday school session,” he said. “They began to appear in schools and other educational institutions, a catch-all technology in the same way that we might use a data projector and a PowerPoint presentation today.”

The fundamental role played by local exhibitors and retailers in the development of a moving-picture industry was also unearthed during the research. Local opticians were able to use their technical expertise to develop substantial hiring and distribution services, particularly libraries of magic lantern slides, which they would rent to customers. One Bristol-based optician was found to have more than 30,000 slides; later, others hosted hundreds of amateur film productions and live performances from their shops.

“If you went to your local opticians, they might have a stock of 3-4,000 lantern slides you could pick from, much like you select something off Amazon Prime or Netflix,” said Professor Plunkett. “You could effectively choose your own box set and have that as a Christmas show or birthday treat – and many opticians would rent out an exhibitor as well.”

Among the showmen and women who toured with magic lanterns and panoramas were Winston Churchill in 1900, who talked about his escape from the Boers; and the controversial American physician Anna Longshore Potts, who presented to exclusively female audiences on the nature of the female anatomy.

Professor Kember said they also discovered evidence of what might be the first-ever mass media political campaign when the Conservative Party used lantern slides and films to deliver messages supporting free trade and anti-immigration in the early 1900s.

“This may represent the first example globally of a screen media-led political intervention,” he said. “And it was met with criticism from the liberal press, who accused the Tories of creating propaganda and trivialising politics with entertainment.”

Camera Obscuras set up in prime ‘people-watching’ spots, including The Hoe in Plymouth and near the Clifton Suspension Bridge in Bristol, were the antecedents of reality TV shows or even CCTV, where you could watch without being observed, said Professor Plunkett.

“We hope the book changes the scholarly and general understanding of the growth of modern media culture and how so many of our contemporary usages of modern visual media have these 19th and early 20th century roots,” says Professor Plunkett.

“We have a preconception that during the 20th century, cinema led to radio, which led to TV, which then became rental and streaming,” adds Professor Kember. “But, by tracking back to the 19th century, we find the beginning of hundreds of other media histories, many of which are still with us today.”

Popular Visual Shows 1800–1914: Picturegoing from Peep Shows to Film is published by Oxford University Press.