Extensive dog diversity millennia before modern breeding practices

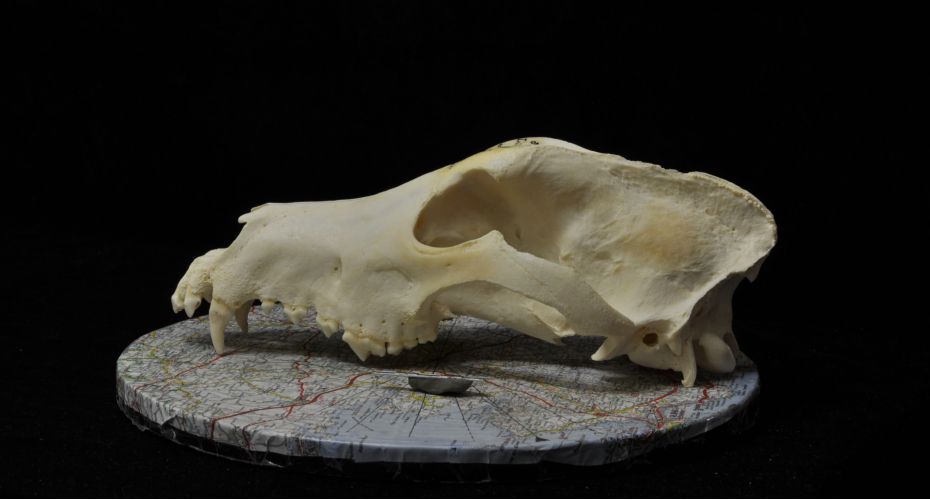

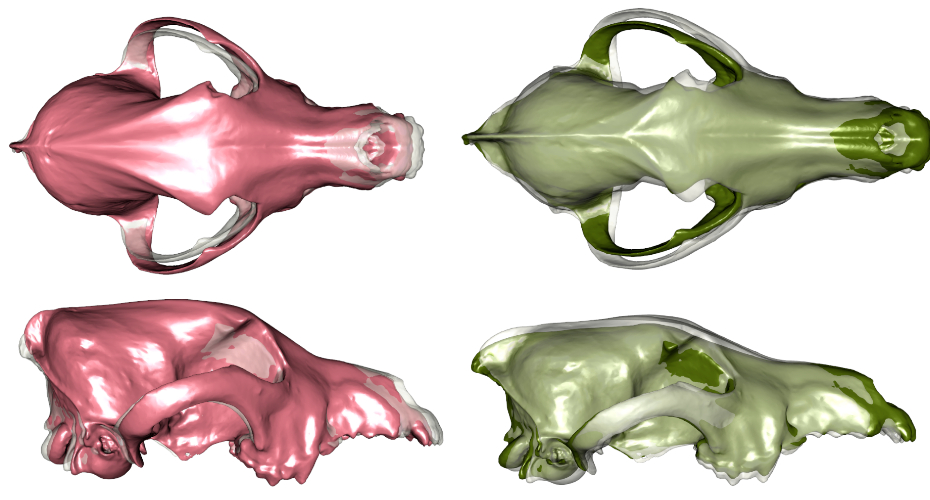

Photograph of a modern dog skull used for the photogrammetric reconstruction of 3D models in the study. Image credit: C. Ameen (University of Exeter)

A groundbreaking archaeological study has revealed when domestic dogs first began to show the remarkable diversity that characterises them today. By applying cutting-edge shape analysis to hundreds of archaeological specimens spanning tens of thousands of years, researchers have traced the emergence of distinct dog forms deep into prehistory pinpointing the moment dogs began to diversify in size and shape – at least 11,000 years ago.

These findings challenge long-standing assumptions that canine diversity is largely a recent phenomenon shaped by selective breeding which started with the Victorian Kennel Clubs. Instead, the study demonstrates that significant variation in skull shape and size among domestic dogs was already present thousands of years ago, soon after their divergence from wolves.

Published in Science and led by the University of Exeter and the French CNRS, the study is the most comprehensive of its kind in terms of both geographic reach and timespan, with specimens ranging from the Pleistocene to the present day. The research, which began in 2014, analysed 643 modern and archaeological canid skulls – including recognised breeds, street dogs, and wolves- spanning the last 50,000 years.

The international team of archaeologists, curators and biologists from more than 40 institutions collaborated to create 3D models of the skulls to study their size and shape using a method known as geometric morphometrics. Results show that by the Mesolithic and Neolithic periods, dogs already exhibited a wide range of shapes and sizes. This variation likely reflected their diverse roles in early human societies, from hunting and herding to companionship.

“These results highlight the deep history of our relationship with dogs,” said co-lead author Dr Carly Ameen of Exeter’s Department of Archaeology and History. “Diversity among dogs isn’t just a product of Victorian breeders, but instead a legacy of thousands of years of coevolution with human societies.”

The earliest specimen identified as a domestic dog came from the Russian Mesolithic site of Veretye (dating to ~11,000 years ago). The team also identified early dogs from America (~8,500 years ago) and Asia (~7,500 years ago) with domestic skull shapes. After that, the study shows a lot of variation emerging relatively quickly.

Dr Allowen Evin, co-lead author from the CNRS based at the Institut of Evolutionary Science-Montpellier, France, explained: “A reduction in skull size for dogs is first detectable between 9,700–8,700 years ago, while an increase in size variance appears from 7,700 years ago. Greater variability in skull shape begins to emerge from around 8,200 years ago onwards.”

She added: “Modern dogs exhibit more extreme morphologies, such as short-faced bulldogs and long-faced borzois, which are absent in early archaeological specimens. However, there is a large amount of diversity among dogs even as early as the Neolithic; it was double that of Pleistocene specimens and already half the range seen in dogs today.”

The study also underscores the challenges of tracing the earliest dogs. None of the Late Pleistocene specimens – some previously proposed as “proto-dogs” – had skull shapes consistent with domestication, suggesting that the very first stages of the process remain difficult to capture in the archaeological record.

Professor Greger Larson, senior author of the study from the University of Oxford said: “The earliest phases of dog domestication are still hidden from view and the first dogs continue to elude us. But what we can now show with confidence is that once dogs emerged, they diversified rapidly. Their early variation reflects both natural ecological pressures and the profound impact of living alongside humans.”

By demonstrating that dog diversity emerged millennia earlier than assumed, the study opens new avenues for exploring how human cultural and ecological shifts shaped the evolutionary history of our closest animal companions.

The article, The emergence and diversification of dog morphology, is published in Science. The research was supported by funding from national and international agencies including the Natural Environment Research Council (UK), the Arts and Humanities Research Council (UK), the European Research Council, the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, the Russian Academy of Sciences, and the Fyssen Foundation.