Rising seas will devastate coastal habitats

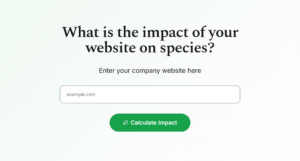

Sea-level rise impacts in the Solomon Islands. Credit Simon Albert, University of Queensland

Research published today in Nature warns that rising seas will devastate coastal habitats.

The study uses evidence that dates back to the last Ice Age. 17,000 years ago, it was possible to walk from Germany to England, from Russia to America, from mainland Australia to Tasmania.

Sea levels were about 120 metres lower than today. But, as the last Ice Age ended, the oceans rose quickly – by one metre per century on average.

The new study, by a global research team led by Macquarie University, warns that rapid sea-level rise and coastal habitat retreat will happen again if the world warms above Paris Agreement targets (1.5-2°C).

The researchers say that key coastal habitats such as mangroves, marshes, coral reefs and coral islands, which are essential to protect coastlines, trap carbon, nurture juvenile fish and help sustain millions of coastal residents, are threatened.

The authors – from 17 institutions in Australia, Singapore, Germany, USA, Hong Kong and the UK – report on how these coastal habitats retreated and adapted as the last Ice Age ended and how they are likely to cope with this century’s predicted sea-level rises.

“Our research shows these coastal habitats can likely adapt to some degree of rising sea levels but will reach a tipping point beyond sea-level rises triggered by more than 1.5 to 2°C of global warming,” said lead author, coastal wetlands specialist Professor Neil Saintilan from Sydney’s Macquarie University.

“Without mitigation, relative sea-level rises under current climate change projections will exceed the capacity of coastal habitats such as mangroves and tidal marshes to adjust, leading to instability and profound changes to coastal ecosystems.”

Mangroves grow in the tropics, predominantly in south and southeast Asia, northern Australia, equatorial Africa and low-latitude Americas.

Coastal marshes grow in intertidal zones further away from the equator, most common along the Atlantic shores of North America and Northern Europe.

“Mangroves and tidal marshes act as a buffer between the ocean and the land – they absorb the impact of wave action, prevent erosion and are crucial for biodiversity of fisheries and coastal plants,” said Saintilan.

“They also act as a major sink for carbon, so-called blue carbon, through absorbing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.”

Mangroves and tidal marshes have some in-built capacity to adapt to rising seas. They do so by accumulating sediment and moving slowly inland.

“Mangroves and other tidal plants have to get oxygen down to their roots to survive, and so that phase of the tide when water drains right out is really important,” said Saintilan.

“When the plants become waterlogged due to higher sea levels, they start to flounder. At Sydney Olympic Park, we’ve seen whole patches of mangroves die when water can’t drain out properly.

“This sort of death would be devastating for many natural mangrove forests across Asia which are restricted in their capacity to retreat from rising seas due to land development and human habitation.”

Co-author Professor Chris Perry, from the University of Exeter, said: “Low-lying coral reef islands are also highly vulnerable to rising seas.

“This vulnerability is projected to increase as sea-level rise rates exceed 6-7 mm per year, and this will have profound consequences for the future habitability of these islands.”

The “health” of the coral reefs that surround reef islands are also key because these form an ecosystem that protects the inner, liveable land from the powerful impacts of the open sea.

“Beyond 1.5-2°C of global warming, you’ll start to see these islands disappear when the waves overtop the coral reefs that protect them,” said co-author Associate Professor Simon Albert, from the University of Queensland.

“In the short term, coastal ecosystems can play a vital role in helping us humans mitigate climate change by taking carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere and offering protection against ocean storms – but we’ve got to help them as well.”