Revealed: genetic process which could be treatment target for deadly fungal disease Candida auris

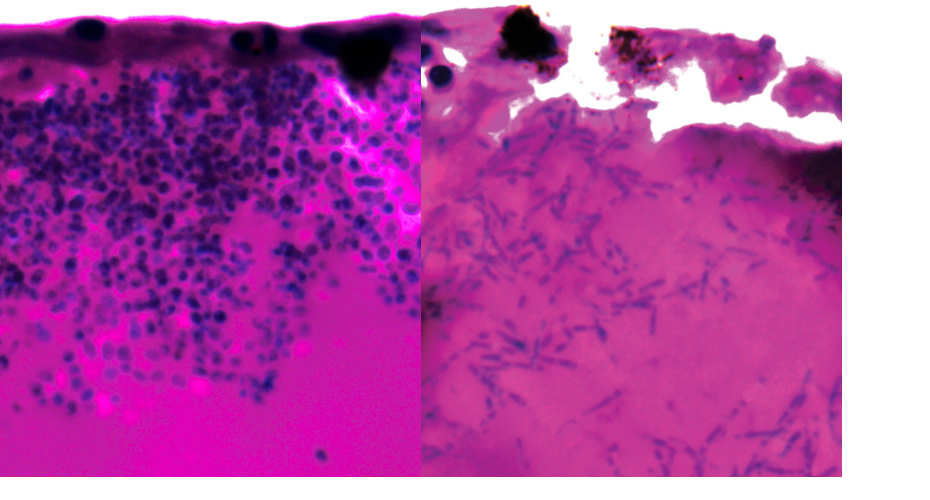

Candida auris during infection. Right hand image shows filaments

Scientists have discovered a genetic process which could unlock new ways to treat mysterious and deadly fungal infection which has shut down multiple hospital intensive care units.

Candida auris is particularly dangerous for people who are critically ill, so hospitals are vulnerable. While it seems to live harmlessly on the skin of increasing numbers of people, patients on ventilators are at high risk. Once infected, the disease has a death rate of 45 per cent, and can resist all major classes of antifungal drugs, making it extremely difficult to treat and eradicate from wards, once patients are infected.

The disease was only detected in 2008, and its origins remain a mystery, but since it emerged, more than 40 countries have reported outbreaks, including the UK. Also known as Candidozyma auris, it has become named a global health threat, and is on the World Health Organization’s critical priority fungal pathogens list. In the UK, the number of cases has steadily risen.

Now, for the first time, researchers at the University of Exeter have investigated how genes are activated during infection using a new approach involving fish larvae. The study is published in Nature portfolio journal Communications Biology and supported by Wellcome, the Medical Research Council (MRC), and the National Center for Replacement, Reduction and Refinement (NC3Rs). The findings show early promise for identifying a target for developing new drugs, or repurposing existing medications, if the genetic process is found to be the same during human infection.

The research was co-led by NIHR Clinical Lecturer Hugh Gifford, of the University of Exeter’s MRC Center for Medical Mycology (CMM), who said: “Since it emerged, Candida auris has wreaked havoc where it takes hold in hospital intensive care units. It can be deadly for vulnerable patients, and health trusts have spent millions on the difficult job of eradication. We think our research may have revealed an Achilles heel in this lethal pathogen during active infection, and we urgently need more research to explore whether we can find drugs that target and exploit this weakness.”

One of the issues so far in studying Candida auris has been its ability to withstand high temperatures. This, combined with particularly high tolerance to salt, has led some to speculate that it could originate from tropical oceans or marine animals. For researchers, it has meant finding a new way to study the pathogen. The Exeter team pioneered a model of Arabian killifish, whose eggs survive at human body temperatures.

The researchers discovered that Candida auris can switch to form elongated bodies of fungus, known as filaments, possibly to search for nutrients.

They also investigated which genes are switched on and off during infection, and therefore could represent vulnerabilities. Genes activated during infection include several that code for nutrient pumps, snatching molecules which scavenge for iron and drawing them into cells.

Co-senior author Dr Rhys Farrer, at the University of Exeter’s MRC Centre for Medical Mycology, said: “Until now, we’ve had no idea what genes are active during infection of a living host. We now need to find out if this also occurs during human infection. The fact that we found genes are activated to scavenge iron gives clues to where Candida auris may originate, such as an iron-poor environment in the sea. It also gives us a potential target for new and already existing drugs”.

Dr Gifford, who is also an intensive care and respiratory medicine resident physician at the Royal Devon & Exeter Hospital, added: “While there are a number of research steps to go through yet, our finding could be an exciting prospect for future treatment. We have drugs that target iron scavenging activities. We now need to explore whether they could be repurposed to stop Candida auris from killing humans and closing down hospital intensive care units.”

An NC3Rs project grant supported the establishment of the Arabian killifish larvae model as an alternative to using mouse and zebrafish, which are used in some studies to study interactions between a pathogen and the host. Dr Katie Bates, NC3Rs Head of Research Funding, said: “This new publication demonstrates the utility of the replacement model to study Candida auris infection and enable unprecedented insights into cellular and molecular events in live infected hosts. This is a brilliant example of how innovative alternative approaches can overcome key limitations of traditional animal studies.”

The paper is titled ‘Xenosiderophore transporter gene expression and clade-specific filamentation in Candida auris killifish (Aphanius dispar) infection’ and is published in Nature portfolio journal Communications Biology.