Archaeologist proposes sustainable approach to research in ecologically fragile areas of South America

The Atlantic Rainforest in Brazil credit Dr Felipe Do Nascimento Rodrigues

Conducting experimental archaeology in ecologically sensitive or fragile areas of the planet presents a fundamental challenge to researchers who are attempting to understand ancient tools and practices.

The need to use samples of native flora and fauna as ‘contact materials’ to test their hypotheses of stone and metal tools can bring archaeologists into direct opposition with environmental legislation and restrictions.

Using non-native proxies for these materials, on the other hand, might address environmental concerns, but risks reducing accuracy of the research.

But now an archaeologist who has spent time working in the protected Atlantic Rainforest area of Brazil has proposed a sustainable-led approach to research that involves collaboration with museums, public gardens and other preservation institutions.

Dr Felipe Do Nascimento Rodrigues, a Doctoral Graduate from the Department of Archaeology and History at the University of Exeter, says that archaeology will also benefit from closer liaison with native populations and legal authorities.

His findings are published in a new report, Conducting use-wear analysis and experimental research in South Brazil: Legal challenges and possibilities, in the latest edition of the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports.

“It is within the context of loss of nature and cultures that contemporary experimental archaeology in Brazil finds itself,” Dr Rodrigues says. “It has great unexplored potential to achieve an in-depth understanding of the techniques and technologies long lost, but to achieve such understanding, detailed and accurate experiments, using relevant contact materials are essential. But the challenge – one that until now has been not addressed – is navigating between dealing with legislation protecting native flora and fauna and using non-native material proxies.”

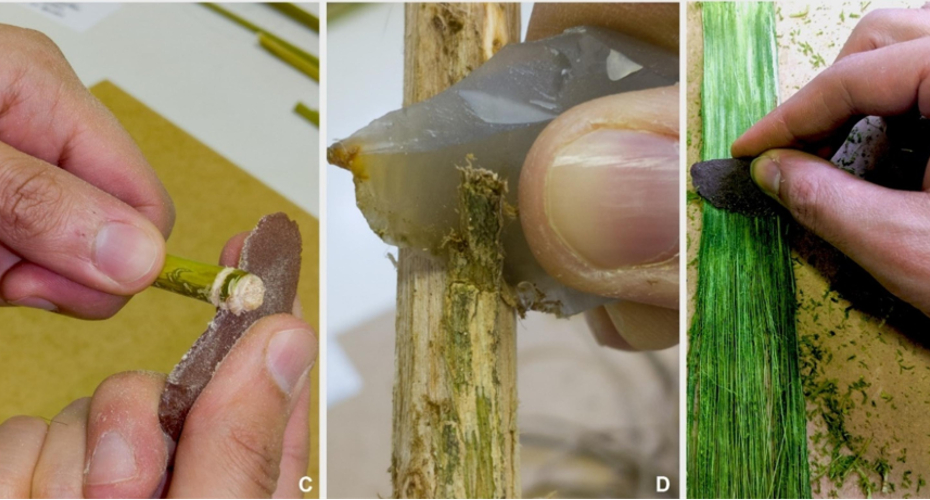

The piece has arisen out of Dr Rodrigues’ PhD work in Rio Grande do Sul, where he was studying the stone tools used by indigenous groups, particularly the Southern Jê, from sites dated between the 9th and 13th century. He examined a range of volcanic, chert and quartz stone tools and how they were used for different tasks, such as de-barking and trimming branches, and fashioning bamboo arrows.

But when it came to sourcing accurate contact materials, Dr Rodrigues found that environmental legislation made it extremely difficult to source them legally – even when some of those plants could be found in civic ornamental displays in the local towns. This is due to the legislation that protects the critically endangered Atlantic Forest, the second largest biodiversity concentration in the Americas, and one that spans Brazil, Paraguay, and Argentina.

Dr Rodrigues began an extensive study of the legislation and of organisations working in the preservation of flora and fauna. Working with the Science Museum at the Universidade do Vale do Taquari and the Botanical Garden of Lajeado, he found he was able to acquire trimmed plant specimens and dead animals destined for taxidermy. As a result, he has now compiled a database of institutions that will be available to researchers working in South America.

“We have gathered the details of 72 institutions so far covering a wide range of biomes, flora, fauna and research interest,” Dr Rodrigues says. “And while this is not envisaged to be an exhaustive list, it will hopefully serve as a good starting point for future researchers.”

Among the other recommendations made in Dr Rodrigues’ paper is the importance of collaborating with native traditional populations on acquiring samples, and engaging with the relevant authorities to find out if they might be granted permission to interact directly with the flora and fauna. And he adds that although his focus here is on Brazil, the principles established could be applied to other sensitive and protected areas of the planet.

“By adopting an environment led practice of experimental archaeology, we can ask questions that are relevant to understanding past problems, while also acknowledging our present reality and the future implications of our research,” he adds.