Coronation 2023: Looking back 70 years to how we celebrated our last royal coronation

In the first in a series of opinion pieces this week that reflect upon the Coronation of King Charles III, Jon Lawrence, Professor of Modern British History, reflects upon how the nation responded to the Coronation of 1953.

Celebrations in Shrewsbury in 1953. Picture by Geoff Charles, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

By Professor Jon Lawrence, Professor of Modern British History of the Department of Archaeology and History.

Because we have not had a royal coronation for 70 years, the rituals and pomp that surround it, and which make it different from other royal celebrations, have largely slipped from living memory. We may have had jubilees aplenty since the late Queen’s Silver Jubilee in 1977, but when we last crowned a monarch, Britain had not yet fully ended wartime rationing and a 38-year-old Stanley Matthews had just inspired Blackpool FC to an historic FA Cup victory.

Not surprisingly, Britain was a very different country in 1953. Its empire had contracted but remained vast. War had ended, but visible signs of its destructive power were still commonplace. Queen Elizabeth was still only 27 years at her coronation, and commentators quickly came to associate her youth (and sex) with the birth of a new ‘Elizabethan age’.

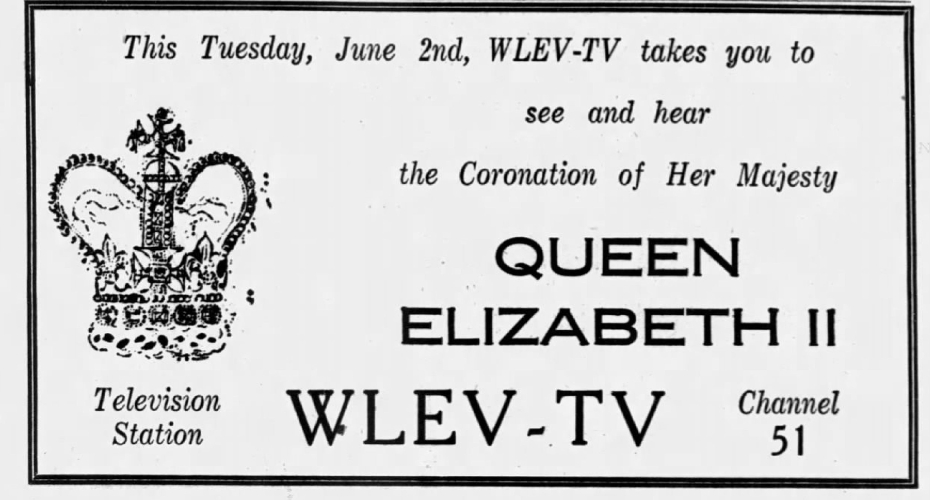

One marker of this new age was that this became the first coronation to be broadcast live to the nation on television (it is true that the BBC had sent its outside broadcast unit to film George VI’s coronation in May 1937, which had in turn sparked a boom in television sales, but even so, fewer than 10,000 households owned a television – it was live radio and cinema newsreels that brought George VI’s coronation to the nation). Television ownership was still low when Elizabeth II ascended the throne on the death of her father in February 1952.

Estimates vary, but probably only about 10 per cent of households owned a set at this point. Two years later that figure was more than 30 per cent. The Queen’s Coronation played a big part in this consumer boom, with widespread reports of a rush to own or rent a television during the long build-up to the event. But what is perhaps more remarkable is that vastly more people claimed to have seen the Coronation on TV than owned (or rented) a television. It is estimated that 27 million people watched the day’s events live on television in June 1953 even though fewer than three million homes boasted a set.

The explanation was simple. Although contemporaries often lambasted television as a threat to community life – as the epitome of the emerging privatised, consumerist society – in 1953, television was a force bringing people together to affirm and celebrate family, community and nation all at the same time.

This was certainly how my late parents always remembered the Queen’s Coronation. They had spent the first year of married life in lodgings, and had only just managed to secure a home of their own. Still childless, unlike many of their neighbours on their new-build suburban estate, my parents were the only ones who managed to secure a television in time for the Coronation. They decided to celebrate this fact (and the Coronation) by inviting their new neighbours round to watch and celebrate together.

In 1937, as children, they had celebrated George VI’s Coronation at a local street party in Redfield, the working-class district of East Bristol where they both grew up. Probably someone had brought a radio out into the street so that everyone could hear the event as the children enjoyed their party. There were still lots of street parties in 1953, but new ways of living and new technologies now made it possible to celebrate in other ways.

Television brought the spectacle of a great state occasion into people’s homes for the first time – except that almost 20 million Britons probably followed the day’s events in someone else’s home or in a communal space such as a pub or club house. Technology brought people together literally as well as metaphorically in 1953. Whether our own new technologies, from social media to streaming services, will have the same effect is less clear.