Archaeological scanners offer 2,000-year window into the world of Roman medicine

The intricate design and workmanship of a set of medical instruments used by Roman surgeons 2,000 years ago have been revealed thanks to state-of-the-art archaeological technology.

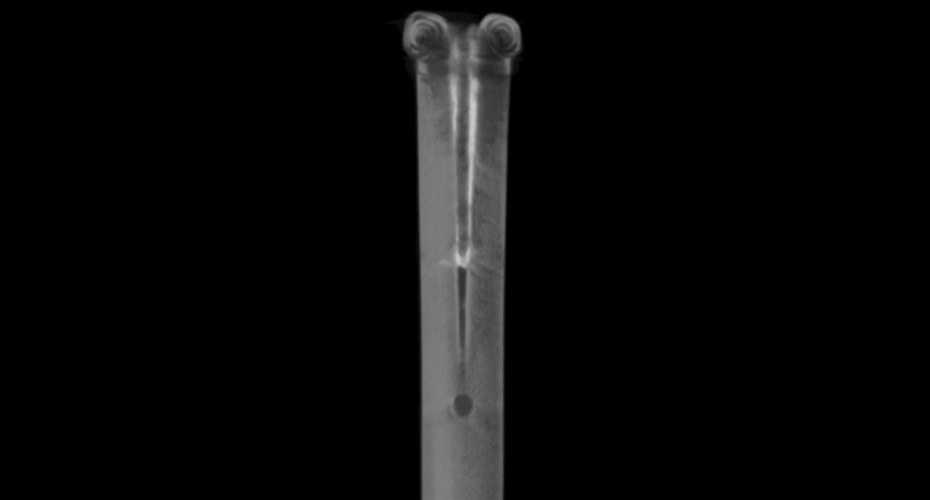

Using a CT scanner capable of peering beneath the surface of objects, researchers have examined six implements including a bronze scalpel handle that would have been used in surgery.

Two surgical probes, a spoon, and two needles were also scanned at the University of Exeter’s SHArD 3D Lab to help build a picture of how they might have been deployed by Roman medics when treating injuries and medical conditions in ancient Britain.

The instruments, held by the Devon and Exeter Medical Heritage Trust (DEMHT), were originally unearthed 125 years ago at a site in Walbrook River, London, which is rich in well-preserved tools and objects from the Roman era. And they have been studied by Professor Rebecca Flemming, Leventis Professor of Ancient Greek Scientific and Technological Thought, as part of her research into ancient medicine and the implements and substances utilised in healing practice.

“New technologies allow us to investigate ancient objects in novel and exciting ways, revealing so much more about their design and manufacture, their capabilities and use,” said Professor Flemming, who is based in Exeter’s Department of Classics, Ancient History, Religion and Theology. “In this case, you can see the attention devoted to crafting the socket where the iron scalpel blade was originally inserted into the bronze handle. The tiny scrolls are both beautiful and functional, making it easier to replace worn blades over the lifetime of the instrument. It is only the bronze that now survives, alongside Greek and Roman medical texts referring to these implements and describing the kinds of surgical interventions in which they were involved.”

Professor Flemming said that Roman surgeons would have used the scalpel for operations and therapeutic procedures such as bloodletting. The probe would have enabled them to make exploratory soundings in advance of surgery such as examining wounds, fistulae and fractures, as well as used to clear wax out of ears. The spoon would likely have enabled surgeons to mix medicaments, while the needles could have sown bandages.

“It is fascinating to find out more about the material in our collection,” said Megan Woolley, co-ordinator of DEMHT. “And having models of historical objects means people can handle them and help us to discover much more about how they would have been used.”

The work was made possible by the University’s Science, Heritage and Archaeology Digital 3D (SHArD 3D) Laboratory, which opened last year thanks to £900,000 of funding from the Arts and Humanities Research Council’s Creative Research Capability scheme. It is the first humanities-led microCT facility in the South West, and enables researchers to create 3D scans of archaeological and cultural artefacts, which are non-destructive to the original.

For the project, the CT scanner generated detailed 3D models of the instruments at a resolution of 0.05mm, and with its x-ray capabilities the researchers have been able to peer below the corroded surface layers to look at the original material beneath. The scans of the instruments will enable exact replicas to be produced through 3D printing, which can then be used for teaching and public engagement.

Dr Carly Ameen, Lecturer in Bioarchaeology in the Department of Archaeology and History, and Director of the Lab, said: “Interdisciplinary research, bringing scientific techniques to bear on historical remains and putting that data into conversation with other evidence, is crucial for developing our knowledge of the past. That is where the SHArD 3D Lab can make a genuine impact, and we are looking to future collaborations in this field.”

“I am interested in the practice of ancient medicine, and also the ways that the Roman empire spread similar kinds of surgical instruments right across their territory, from Britain to Syria,” adds Professor Flemming. “And what this project also reveals is the potential we have here to bring heritage organisations such as DEMHT together with the technologies of SHArD 3D to explore common questions and aims.”