Coronation 2023: Devon’s leading coronation roles

In the second opinion piece of the week, Professor James Clark considers the coronation guest list – and the role that Devon has played in ceremonies past.

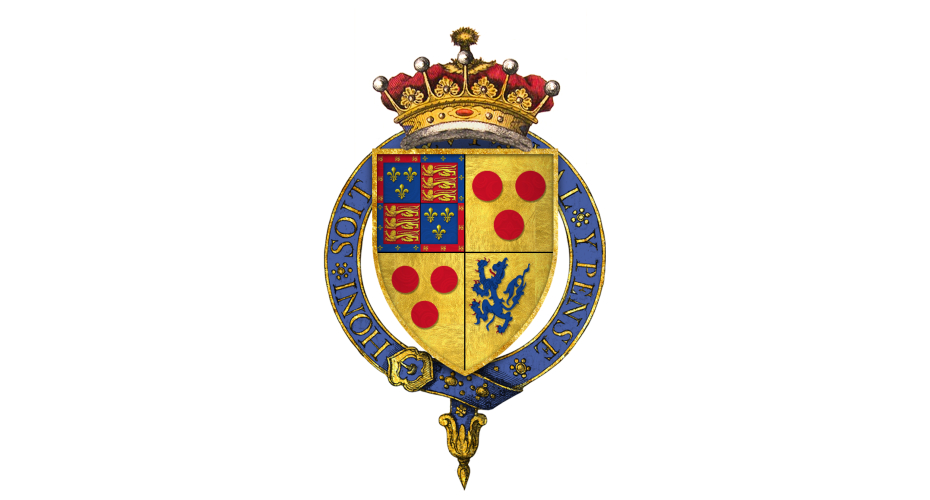

Coat of arms of Sir Henry Courtenay, 10th Earl of Devon, via Wikimedia Commons

By Professor James Clark, Associate Dean for Research and Knowledge Transfer, and Professor of History, in the Department of Archaeology and History.

It’s set to become the most talked-about invitation of the decade. Already, even before the first sighting of the gilded coach, or the crowded abbey church, there is fall-out from the guest-list; of course, those who didn’t make the cut as much those who did.

The public chatter and the personal bitterness are nothing new. It may be magnified because monarchy today is under a mass-media spotlight but coronations have always been a focus for political controversy – international, national, regional and also, the politics within the royal family itself.

Naturally, in the 21st century the primary concern for Buckingham Palace and for Downing Street is to approach the ceremony as a PR reception for the world. In centuries past, the target audience was much closer to home. Before the media age, the person of the monarch and the performance of monarchy were remote, shrouded in mystery and more-or-less invisible to the majority of their subjects. Quite literally, they had to be seen to be believed; and when they were witnessed, it was essential that the leading figures of the nation – representatives of government, church, the law and the landing-owning classes – were standing alongside.

It was not by chance that when the 19-year old Queen Victoria processed into Westminster Abbey for her coronation in 1838, the ancient role of sword carrier was taken by the Prime Minister, Lord Melbourne. The new reign of the teenage queen required the reinforcement of the head of the elected government.

In a pre-industrial age, it was especially important for the incoming monarch to win the backing of the regions. The counties of England and Wales were encouraged to invest in a coronation through customary contributions that cities, towns and titled families made towards the ceremony. For example, the Lord of the Manor of Liston (Essex) was responsible for presenting five wafers before the crowned monarch at the coronation feast. Successive Lords did just this, from the coronation of Richard II (1377) to that of James II (1685).

The county of Devon accrued more of these honours than most. It was an Ottery St Mary naval officer, Isaac Heard (1730-1822), who as royal herald, Garter King of Arms, proclaimed the accession of King George IV on 31 January 1821. Heard had served king and country from the rank of Midshipman at the age of 15; his pivotal part in the making of his monarch came to him in his ninetieth year.

Devon was long a recruiting-ground for military service and the county’s sailors and soldiers were often rewarded for their valour with a front-row seat in the coronation festivities. Edward Giles, of Ashprington, near Totnes, led the defence of the West Country coastline when threatened with Spanish armadas in 1596, 1597 and 1601; later he served with Queen Elizabeth I’s army supporting the Dutch in their battles with the colonial power of Spain. Giles’ prize was a knighthood conferred on him by the new King James I at his coronation in July 1603.

He belonged to an ancient tradition of prized fighters presented at the coronation. William Martin of Combe Martin saw action with Edward I (1272-1307) and his son on the battlefields of France, Scotland and Wales. Finally, as a seasoned campaigner aged 50, he was summoned to be knighthood in the coronation honours of Edward II in 1308.

Devon’s earliest and most enduring coronation role was won even further back in time. When King Richard I – the crusading monarch known as the Lionheart – was freed from captivity, he presented himself to his English subjects for a second coronation at Winchester in 1194. His loyal supporter, William de Vernon (d. 1217), baron of Plympton and earl of Devon, was given perhaps the greatest honour in the medieval ceremony of coronation, that is to raise the cloth of gold canopy over the king at the climax of the ceremony to conceal the secret magic of his anointing.

When the earldom of Devon passed on to a new family line, the Courtenays, it carried with it a tradition of a main-cast role in coronations.

When the ten year-old King Henry VI was processed to the altar of Paris’ Notre Dame Cathedral to be crowned King of France in 1431, Thomas Courtenay, earl of Devon, (d. 1458), himself only 17, followed in his train. And when Henry Tudor entered Westminster Abbey for his crowning in 1485 after his defeat of Richard III on Bosworth Field, Earl Edward Courtenay of Devon (d. 1509) was ceremonial sword carrier.

Earl William Courtenay (d. 1511) reprised his father’s role at the coronation of Henry VIII and Queen Katherine of Aragon in 1509. Now, there was a determination to set Devon’s primacy in stone, and the earl’s claim to carry the sword was written up in the Tudor Device, or order of ceremonies for the coronation.

William’s son, Henry Courtenay, Marquis of Exeter (d. 1538), was Henry VIII’s favourite for nearly two decades but then he fell foul of the king’s suspicions, was arrested, executed and his family stripped of the title and their Devon territory. Their star-part in the coronation procession was lost, although in 1554 Henry’s son Edward was invited to carry the ceremonial sword as Mary Tudor made her entrance to her coronation banquet.

In spite of the traditional symbols displayed in the colourful invitation, in 2023 the approach to the coronation guest-list and the ceremony is entirely present-minded. A call came out from the Cabinet Office for customary claims to be examined but even those with the deepest roots wound around our royal history knew that the tide of the times was against them.

No bad thing, perhaps, for the tradition of monarchy today to take a truly contemporary frame. But the case for a connection between royalty and region, capital and county, should not be forgotten.

Naturally, in the 21st century the primary concern for Buckingham Palace and for Downing Street is to approach the ceremony as a PR reception for the world. In centuries past, the target audience was much closer to home.

Professor James Clark