Major new exhibition shows impact of Gertrude Bell on the Middle East and international political history

Gertrude Bell had a keen interest in the Middle East, its history, people, culture and politics and documented her experience and travels

A major new exhibition examines the pioneering explorations of Gertrude Bell in the Middle East, and the political legacy of her activities in the region.

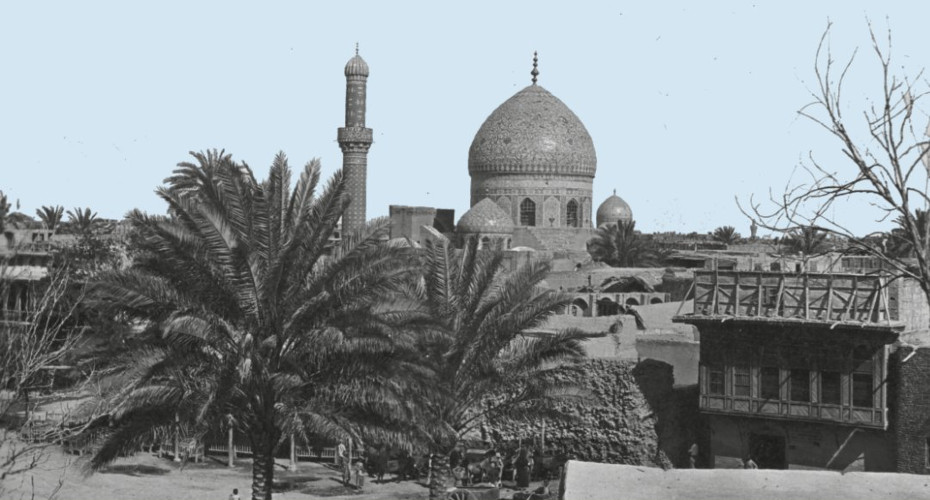

The traveller, archaeologist, photographer, writer, and political officer documented the ethnic, tribal and religious diversity of Mesopotamia through her pictures and writings. She photographed and mapped many significant European and Middle Eastern archaeological sites, and later had an instrumental role in the formation of the modern state of Iraq.

Archive material displayed as part of the exhibition shows the complexity of Ottoman government’s perception of Bell’s overlapping identities: a traveller, a photographer/archaeologist, and a political agent or spy. It also shows her views on Kurdish political power.

The exhibition, at University of Exeter’s Institute of Arab and Islamic Studies, was put together in partnership with Newcastle University to consider particularly Bell’s role in the British administration in Mesopotamia and then following the establishment of Iraq in 1921

Gertrude Bell had a keen interest in the Middle East, its history, people, culture and politics and documented her experience and travels. In later life she played a key role in the founding of the Kingdom of Iraq.

During World War One she joined the Arab Bureau, working alongside colleagues such as T.E. Lawrence – “Lawrence of Arabia” – to provide information on the geography and tribes of the Middle East. Her work helped the British Army to plan their movements and identify tribes willing to join the War against the Ottoman Empire. This helped to facilitate the military uprising known at the Arab Revolt in 1916.

Bell travelled to Baghdad in 1917 and continued her intelligence work, writing reports and dispatches for the War Office. She was the only female political officer in the British forces and later received a CBE for her work. She remained in Baghdad for the rest of her life, dying in 1926, one month after the northern border of Iraq had been settled between the British and Turkish governments.

University of Exeter historian Dr Semih Celik has contributed archival material from the Presidential Ottoman Archives in Istanbul which confirms the Ottoman government’s close surveillance and negotiation of Bell’s activities. It shows they saw Bell as a photographer and archaeologist whose activities were useful in documenting Islamic heritage but also a political agent and tried to stop her from travelling, often without success.

Dr Celik said: “I believe Bell was unique in the way she negotiated different overlapping identities during the different phases of her travels into Asia Minor and Mesopotamia. Her letters testify that despite her dislike of bureaucratic procedures and formalities, she showed respect required of her to Ottoman bureaucrats and officers. Her linguistic skills, knowledge of the landscape, society and culture allowed her the space to negotiate terms of her activities in the Ottoman territories carefully.

“Correspondence by the interior ministry about her early travels said her political ideas conflicted with Ottoman interests. When the Ottoman authority in Mesopotamia was weakened by the beginning of WW1 she was seen more as a political agent of the British imperial machinery and a spy.”

Dr Farangis Ghaderi, Director of the University of Exeter’s Centre for Kurdish Studies, used the university’s Kurdish archives, as well as documents in archival centres in Iraqi Kurdistan and private archives to put together parts of the exhibition which show Bell’s views on Kurds and her opposition to Kurdish political aspiration for independence. The documents also illustrate the Kurdish resistance against the integration of Southern Kurdistan to Iraq.

Dr Ghaderi said: “Prior to the Cairo Conference in 1921, Bell favoured a form of ‘local Kurdish autonomy’ within the general administration of Mesopotamia. Following the shift in British imperial policy from direct rule to the mandate system and the development of British-Arab relations, she came to consider autonomous Kurdish rule as a threat to the unity of the Iraqi state.”

“The exhibition shows Bell’s attitude towards Kurds and the fateful effect of her views on the future of Southern Kurdistan. It also highlights Kurdish resistance and the role of the Kurdish leader Shaikh Mahmoud Barzanji Malik in leading a series of uprisings against the British. The exhibition also illustrates how both the British and the Kurds used print media to advance their politics.”

Significant parts of the exhibition were shown earlier this year at the Great North Museum Hancock in Newcastle upon Tyne as the result of a three-year project by Newcastle University’s Special Collections & Archives generously funded by the Harry and Alice Stillman Foundation to digitally curate the UNESCO Gertrude Bell Archive. University of Exeter experts have contributed to this new version of the exhibition to reflect the perspectives of Kurdish and Ottoman communities on Bell’s work.

Professor Mark Jackson, from Newcastle University, said: “This new exhibition incorporates contributions from the IAIS the University of Exeter enabling us to share some of the very important archival material and research of our two institutions for this significant period.”