Move on from “wise old judges” to learn from the 21st century’s most worrying problems, experts urge

An audiobook is being created to mark five years since the crisis hit Britain

Moving on from inquiries led by the “wise old judge” could help politicians and others to prevent and learn lessons from the most worrying problems of the twenty-first century, experts have said.

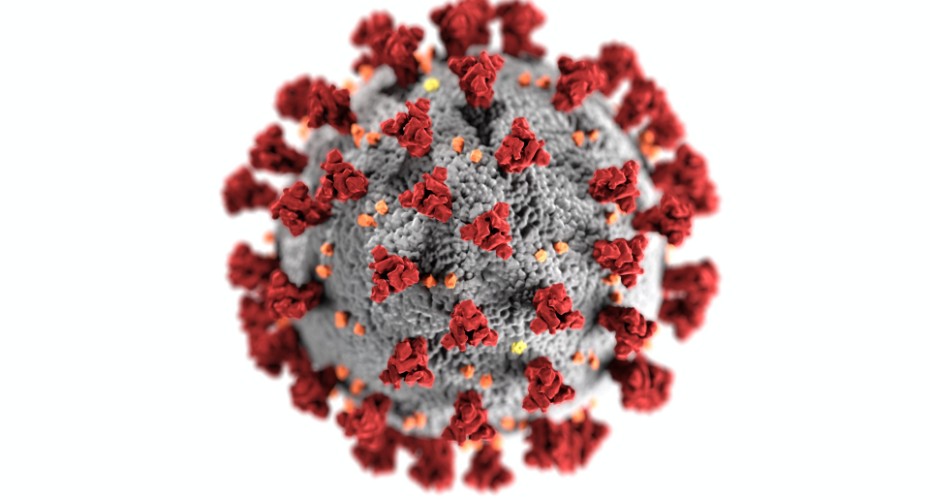

Using other methods rather than a judge-led public inquiry could lead to better learning and prevention, and this should be considered as the COVID-19 inquiry gets underway.

A tendency to adopt forensic style investigations, with enforcement of the production of evidence readily backed by the courts, with the apportion of blame, threatens to overshadow the important understanding of more deep-rooted societal issues, according to researchers. It can also lead to individuals being reluctant to help inquiries find the truth for fear of personal consequences.

Sarah Cooper and Owen Thomas, from the University of Exeter, writing in the book “New Directions In Royal Commissions & Public Inquiries: Do We Need Them?” say the juridical approach is well-suited to investigate fine-grained behaviour in a discrete event but less capable of addressing complex sociological and structural pathologies.

Dr Thomas said: “Full statutory inquiries are well suited to address troubling events that have discrete timelines and where fact-finding rests on the forensic tracing of individual knowledge and behaviours. This, in turn, facilitates the attribution of responsibility and the identification of regulations that might prevent future occurrences. But juridically-minded inquiries are often reluctant to engage with complex sociological phenomena because they may fall outside of the expertise of those involved, or because it is thought matters should be left to elected politicians.”

Dr Cooper said: “The key to an effective coronavirus inquiry will be a range of expertise – such as public health, medicine, statistics, epidemiology, economics, and policy-making – who can uncover facts from archival evidence. The popular cultural desire to put the government ‘in the dock’ would, in this case, be counterproductive.”

A total of 32 public inquiries have been appointed since the UK’s Inquires Act 2005, of which are 15 currently ongoing. These include full statutory versions, ranging from the Edinburgh Tram Inquiry to the Death of Dawn Sturgess, plus less formal, ad hoc investigations including non-statutory inquiries, independent panels and Royal Commissions.

There were almost 400 Royal Commissions between 1830 and 1900 but only three have been set up since the 1990s. In 2019, however, both the Conservative and Labour manifestos promised Royal Commissions across the criminal justice system, substance abuse, and health and safety legislation.

Royal Commissions focus on widespread policy problems rather than discrete events. The study says they could complement other public inquiries by providing a system within which to examine complex challenges – such as institutional racism, misogyny or wealth inequality.

The frequency of inquiries has increased significantly since the 1990s. The study says this may reflect a broadening of public outrage into areas of social risk such as child abuse and medical malpractice. It may also demonstrate a growing tendency by the government to use inquiries as part of a blame avoidance strategy that allows governments and ministers to refrain from addressing the issue for as long as the investigation continues.

Dr Thomas said: “Judicially led and juridically minded inquiries have important limitations: they are reluctant to investigate widespread, historically embedded social issues such as racism or gendered inequalities, and the courtroom style of investigation can lead to adversarialism that impedes openness and candour.”

Out of 76 inquiries undertaken since 1990, 53 were chaired by current or retired judges. Inquiry members are often older, white and male. Between 1990 and 2017, there were just six inquiries with a female chair – which is the same as the number of inquiries led by someone called Brian and fewer than the number of inquiries chaired by someone called either Anthony or William.

Dr Cooper said: “Moving beyond the lure of the inquiry led by the wise old judge, toward some of the instruments of the past, could be an important development in preventing and learning lessons from the most worrying problems of the twenty-first century.”