Research uncovers how the Valentine’s Day Telegram provided ‘love on delivery’ to revitalise the holiday tradition

PhD student Megan Furr makes a remarkable Valentine’s discovery during the course of conducting research into the British inland telegraph system.

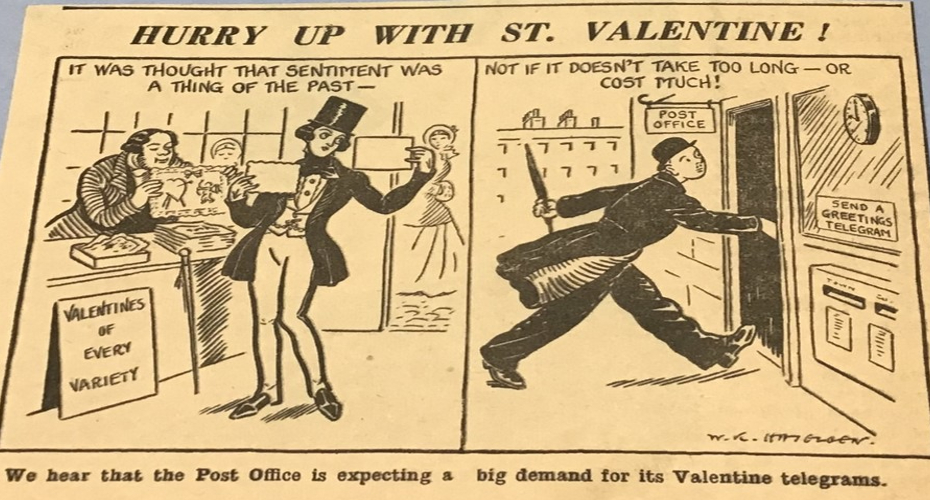

A newspaper cutting from the 1930s advertising the St Valentine's Day Telegram service

New research has revealed how Valentine’s Day telegrams in the years surrounding World War Two played an important role in revitalising the traditions of the romantic holiday and rejuvenating the telegram service itself.

Local newspaper reports unearthed by a young historian show how the Valentine’s Telegram was created in 1936 to dispel the association of bad news with the popular form of communication.

The service, created by the General Post Office, transformed telegram messengers into cupids, and saw psychologists, artists and even film makers consulted and hired to perfect the design of the telegrams and their envelopes and advertise it under the brand of ‘love on delivery’.

These insights have emerged as part of a collaborative PhD on the British inland telegraph network, funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council, and undertaken by postgraduate research student Megan Furr, with the University of Exeter and BT Group Archives.

Megan, who is based in the Department of Archaeology and History in Penryn, said that she began to investigate the history of Valentine’s telegrams after finding a film stored in the BT Group Archives film collection entitled Heavenly Post Office.

“The telegram had, during World War One, become associated with the delivery of bad news, which only served to exacerbate its decline, owing to competition from the telephone,” said Megan. “So, the introduction of the Valentine’s Telegram in 1936 proved a hit for the Post Office. It not only extended the life of the telegram, but also reinvigorated the tradition of Valentine’s Day, which was enduring a marked dip in popularity from its Victorian heyday.”

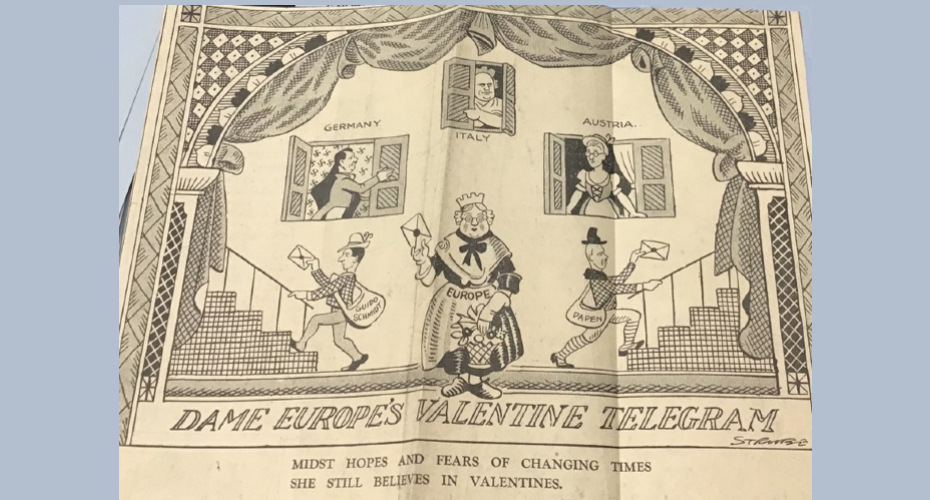

While conducting research into the history of the telegraph network at BT Group Archives and the British Postal Museum Archive, Megan came across a wealth of archive material, including adverts and newspaper cartoons that revealed the benefits of the service – which by necessity, was short and inexpensive. Cross-referencing this information with accounts in the local media, stored on the online British Newspaper Archive, Megan began to construct a picture of how the service was received by the public.

She found reports which demonstrated the popularity of these new telegrams from Middlesbrough to Plymouth, where it was suggested that ‘Cupid had scattered his supply of darts more generously than ever before’; a fight which broke out involving around 100 women in an Oxford Street store that had a small supply of telegrams left; and a golfer in Leeds being pranked by friends after he was sent scores of them.

Megan said: “Some of the coverage poked fun at the Post Office for framing itself as ‘coming to the aid of Cupid’ while using the romantic occasion to make money. It was a sentiment perhaps captured best in the following rhyme: ‘I wire my plea beloved mine; Will you be my Valentine? Hell, that cost me three shillings nice!’”

Also referenced in local newspaper reports was the ‘love code,’ which was created by the General Post Office during World War Two to reduce the strain on the telegraph system and facilitate more rapid delivery of messages. Upon realising the same phrases kept repeating themselves in the telegrams sent to soldiers stationed overseas, more than 100 of the most used phrases were given corresponding numbers. It was this number that was telegrammed to the operator, who would transcribe it and produce the physical telegram that would be given to the recipient.

“This system made it much quicker and easier to get messages to and from different locations and was designed to free up the network at a time when the British public was encouraged to reduce their use of the telegrams “says Megan. “The Post Office assured those sending these telegrams that ‘every degree of affection would be provided for’. We know there were phrases such as ‘Wish we could be together on this special occasion’, ‘You are more than ever in my thoughts at this time’, ‘love and kisses’, as well as messages such as ‘you have a son’ or ‘you have a daughter’.”

It is hoped that Megan’s Collaborative Doctoral Partnership with BT Group Archives, entitled ‘British Telegraphic Work and Spaces, 1840-50,’ which involves the study of a wealth of largely unexplored material, will yield more new insights into the inland telegraph network.

The introduction of the Valentine’s Telegram in 1936 proved a hit for the Post Office. It not only extended the life of the telegram, but also reinvigorated the tradition of Valentine’s Day, which was enduring a marked dip in popularity from its Victorian heyday.”

Megan Furr