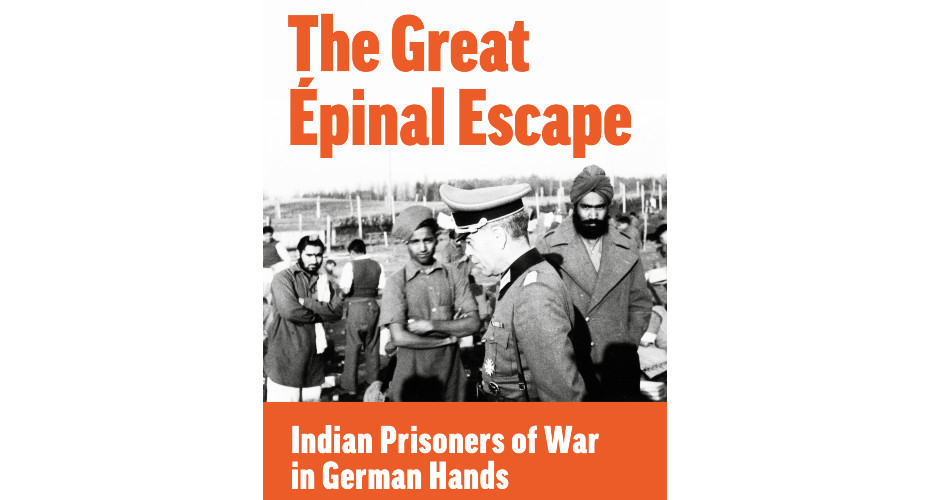

First research published into largest successful World War Two prisoner of war escape

Dr Ghee Bowman has told the incredible story of these men for the first time

It was the largest successful prisoner escape of the Second World War – taking place just six weeks after the more famous ‘Great Escape’ from Stalag Luft III.

But until now the story of the 500 Indian men who daringly ran from a Nazi camp in France and made it to safety in Switzerland has been curiously poorly known. No film has been made, and no book written of this astonishing feat.

Now a historian is working to correct this. Dr Ghee Bowman has told the incredible story of these men for the first time, as well as the experiences of the 15,000 Indian soldiers held by the Nazis in Europe.

Their determination and resilience was echoed by the French villagers who aided their journey. Later in 1944 some were murdered by the Nazis.

More than 3,000 Indian prisoners of war were brought to a camp in Épinal on the Moselle river from across the Third Reich.

Prisoners escaped when US bombs fell on it, piercing the wall. The Hindu, Sikh, Muslim and Gurkha prisoners – many of whom had made escape attempts previously – grabbed food and clothes and ran, dodging German bullets. They knew that the Swiss frontier was just 100 kilometres away to the south, and that, if they could cross the border, they would be safe. On the way they hid in the fields, mountains and forests of eastern France.

The soldiers escaped the camp on 11 May 1944, just before D Day. The quickest groups reached Switzerland in five days, while 500 had arrived by the end of June.

The Swiss government placed them in different camps around the country. When French borders began opening up the soldiers moved to the South of France, then Italy and Egypt before going back to India at the end of the year.

Dr Bowman, an expert on the Indian Army and the Second World War from the University of Exeter, said: “The scale of this escape was extraordinary, and it is a travesty the story isn’t better known in India and Britain. Was it because they were Indian troops, D Day or because of concern for other British soldiers held as prisoners of war and French citizens?

“My research continues too, I would love to hear from any veterans and their families who have any information or memories.”

Dr Bowman heard the story of escapees when he was researching another book on Indian soldiers serving in Europe, The Indian Contingent. As part of his research he met the families of escapees and relatives of those who helped them in France, as well as examining documents in the British Library and National Archives, the Red Cross and from the Swiss federal archives.

A memorial to the murdered French citizens was unveiled on 7 September 1947, and the village was awarded the Croix de Guerre and the Légion d’Honneur, with representatives from India and Pakistan attending the ceremonies. Prior to that was a ceremony in October 1946, before the memorial was ready, and before Partition. Colonel Hayaud Din represented the Indian Army, and Sir Samuel Runganadhan – the last High Commissioner of India to London – gave a speech of thanks, presenting a cheque for £1,000 to the memorial fund, and a smaller cheque for the establishment of a library to serve Étobon and Chenebier.

A plaque from the Indian government was installed in the village in the late 1940s marking the escape

News of the escape reached the War Office in London from Henry Antrobus Cartwright, the British Military Attaché in Bearne, on the morning of Sunday, 21 May 1944, the day after The Times had published a short article on the escape from Stalag Luft III.

It read: “Swiss internal authorities inform me that up to midday today 186 Indian prisoners of war who escaped from camp near Epinal as a result of recent bombing there have entered Switzerland and are at present being kept in Porrentruy district. One man was killed by Germans when swimming a river on the frontier and his body was recovered by fellow escapers.”

Three days later a further telegram arrived from Berne, with information gleaned from escapers. It gave the names of some of the prisoners, details the bombing by the Americans and the loss of life, and relates some of the circumstances of the journey to the neutral frontier. It said the total number of escapers in Switzerland had reached 278.

The escapers included Barkat Ali from Punjab, who is buried in a cemetery at Vevey beside Lake Geneva. There was also a Gurkha called Harkabahadur Rai, who escaped and joined the French Resistance in a fierce battle in the mountains south of Belfort. Their comrade A.P. Mukandan was a postman by trade, captured at Mersa Matruh in Egypt in 1942. He escaped from Épinal but was recaptured.

During World War Two Sikhs, Muslims, Hindus, Indian Christians and Gurkhas from right across South Asia were taken prisoner in North Africa, France, Italy, Greece and Ethiopia, and on the high seas. They endured up to five long years behind barbed wire, making music, learning languages, grumbling about the food and praying to God. Dr Bowman has built a database with the names and service information of 12,000.

When they returned to India escapees weren’t feted and greeted and welcomed back as heroes at the end of the war, nor with the passage of time. Some of the Épinal escapers waited six months for back pay. There was also bad feeling about the lack of medals and awards. Morale among returning POWs was low.

Many prisoners had learnt languages. They became generals, ambassadors, farmers, teachers – bringing back what they had learnt in Europe, their enhanced political and social awareness helping to build their new countries.

Of the 6,000 European graves and memorials to Indian soldiers on the Commonwealth War Graves Commission website, Dr Bowman has identified 248 as POWs.

In late 1945, an Indian Military Mission opened in Berlin, charged with tracing missing POWs and locating graves. From August to December 1946, they supervised excavations of bomb craters at Épinal. Sixty-four bodies were found, but most were not identified. The mission completed its work in 1946 with 125 men still listed as missing. The work of locating them continues.

In 1954, a grave marked ‘Un Français Inconnu’ (‘an unknown Frenchman’) was dug up and found to be wearing British khaki. He was identified as Dafadar Jodha Ram from Chauki Kankari, near Hoshiarpur, and he was later reburied at Épinal.

More recently, the headstone of a soldier from the Baluch Regiment was discovered in a ditch in Waregem in Belgium. It turned out be a duplicate of that of Salim Makhmad, killed on 11 May in the bombing of Épinal. How it came to be in that ditch, 400km north-west of Épinal, is yet to be established.

When the authorities in Épinal started excavations for a new gendarme barracks next to the site of the camp in the 1970s, several bodies of Indian soldiers were discovered.

An Indian edition of the book will be published in January by Westland Press.