The Last of Us: could it really happen?

Guest post by Professor Elaine Bignell, an expert in fungal lung infections at the University of Exeter’s MRC Centre for Medical Mycology – the largest centre of its kind in the world.

HBO aired the final instalment of The Last of Us this week, with millions of viewers watching the post-apocalyptic drama unfold over nine episodes.

Set 20 years after a fungal pandemic, the series begins with a fictional Professor of Medical Mycology identifying the causal fungal species as Ophiocordyceps unilateralis. This ant-infecting fungus that manipulates the behaviour of its prey, the so-called “zombie-ant fungus” causes infected ants to climb upwards in forests to enable the fungal spores to be more widely distributed from the dying corpse.

The graphic depictions of a planet ravaged by killer fungi, and zombified human victims of the pandemic, have prompted widespread concerns about the likelihood of a fungal pandemic. Around the globe, Medical Mycologists – who study fungal infections – have engaged in interviews and podcasts to address the important questions this raises.

The most common question that has arisen is: could it really happen?

The simple answer is yes – but not in the way we have recently seen unfolding on TV.

Fungi that we currently regard as posing significant threats to human life do not cause disease on the scale we have seen in The Last of Us.

Firstly, most human-infecting fungi are not able to overcome a healthy human immune system. There are some exceptions to this rule, including several fungal species endemic to specific geographical regions of the Americas and whose distribution is widening due to climate change.

Secondly, fungal infections don’t usually spread from person to person – most are acquired from the natural environment via inhalation of spores – or caused by resident fungi of our own microbiomes.

Mark Ramsdale, Associate Professor in Molecular Microbiology at the University of Exeter said: “It’s unlikely that a fungal disease could spread on the scale we have seen in The Last of Us. Fungi can change people’s behaviour, though – psilocybin is found in hundreds of species of fungi. Magic mushrooms, for example, manipulate their host and are well known to affect mood, body temperature and sexual desire.

“Fungi have long been associated with psychic episodes. Claviceps purpurea is an ergot fungus which may have been associated with the “Dancing Plagues” – psychic epidemics dating back to the Late Middle Ages and potentially linked to consumption of infected rye.”

Ergot fungus can cause hallucinations and has also been associated with witchcraft in the past.

There’s also the famous fly agaric toadstool, Amanita muscaria – so named because eating it can give you the psychic experience of “flying” – which is still used in some quasi-Christian religious ceremonies by witchdoctors in parts of Mexico and central America.

Just because we are unlikely to be zombified by fungi, though, doesn’t mean we should ignore the fact that fungi can be dangerous. Fungi are already major, neglected causes of fatal human disease.

Invasive fungal diseases are often fatal if untreated and have recently been highlighted by the World Health Organisation as being major causes of human death and disease that will require significantly more research and specialists to overcome. Pathogenic fungi infect over a billion people each year causing 1.6 million deaths (on par with malaria or tuberculosis) and are becoming increasingly resistant to the few available antifungal drugs.

Fungal pandemics and outbreaks that are currently taking place include:

Candida auris – affecting humans, often multi-drug resistant and has caused outbreaks in healthcare settings, and can cause serious illness including bloodstream infections in hospitalised patients.

Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis – affecting amphibians, this fungal disease has moved across globe (possibly through pet trade of African clawed frog) and devastated amphibian populations, in a global decline towards multiple extinctions.

Neil Gow, Deputy Vice-Chancellor for Research and Impact and Professor of Microbiology at the University of Exeter, said: “The four fungal species that the WHO have identified as the most critical threats to human health are amongst those studied intensively at the MRC Centre for Medical Mycology, which aims to find new treatments for fungal infections and diagnose them more quickly.”

“It’s so important to raise awareness of this crucial threat to human health, and we hope that this will lead to more investment in research.”

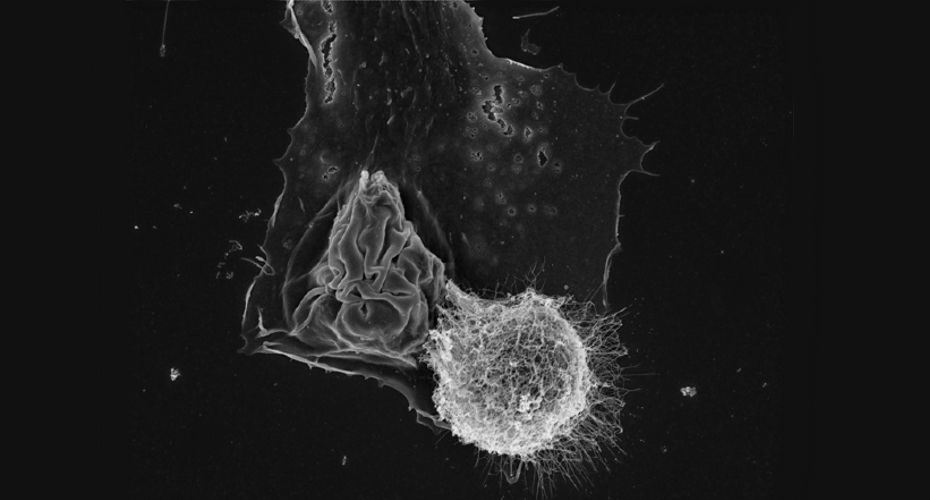

Image credit: Scanning electron micrograph of crytococcus conidia interaction with immune cells (so called macrophages and dendritic cells). Courtesy of Dr Carolina Coelho at the MRC CMM.

More Information

To find out more about expertise at the MRC Centre for Medical Mycology, visit www.exeter.ac.uk/medicalmycology.